SHAPE: A FOUNDATIONAL GUIDE

An Essential Element of Visual Language

What is Shape in Art?

In visual art, shape refers to a two-dimensional, enclosed area. It can be defined by boundaries such as lines (where the beginning point meets the ending point), color, value, or texture.

Vincent van Gogh, The Sower, 1888. Photo by jankie via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

As seen in the painting above, shapes are defined by expressive lines, vibrant color contrasts, dynamic shifts in value, and thick paint textures.

Shape vs. Form: What’s the Difference?

While the terms “shape” and “form” are related and often used interchangeably, they actually refer to distinct concepts in art. Form can encompass the overall visual organization of a work, including not just shape, but also color, texture, and composition.

| Term | Dimension | Defined By | Example |

| Shape | 2D | Enclosing line, color, or value – flat | Circle, silhouette of a person |

| Form | 3D | Volume and mass with depth | Sphere, sculpture in space |

Shape

Form

Types of Shape

Shapes are generally classified into two broad types:

➤ Geometric Shapes → clarity, professionalism, stability

Piet Mondrian, Composition ll in Red, Blue, and Yellow, 1930. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

- Definition: Regular and mathematically defined

- Examples: Circles, squares, triangles, rectangles

- Associations: Order, structure, logic, and human-made environments

- Used frequently in architecture, graphic design, and abstract art

➤ Organic (Freeform) Shapes→ warmth, creativity, natural appeal

Jean Arp, Abstract Composition, Construction Paper, 1915. Image courtesy of WikiArt

The Psychology and Symbolism of Shapes

Shapes also carry psychological and cultural meanings. Here are a few examples:

| Shape | Type | Key Traits | Symbolism |

| Circle | 2D | No corners, equidistant points | Unity, harmony, eternity |

| Square | 2D | 4 equal sides, right angles | Stability, balance |

| Triangle | 2D | 3 sides, pointed | Energy, direction, transformation |

| Organic | 2D/3D | Irregular, freeform | Creativity, fluidity, the natural world |

Circle

Yayoi Kusama. Photo by Lizzy Shaanan Pikiwiki Israel in 2022

Square

Josef Albers’ Studies for Homage to the Square, 1967. Image courtesy of Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, TX, US

Triangle

Henri Matisse, 1953

Organic

Roberto Matta, Glande fiction, 1938. Image courtesy of WikiArt

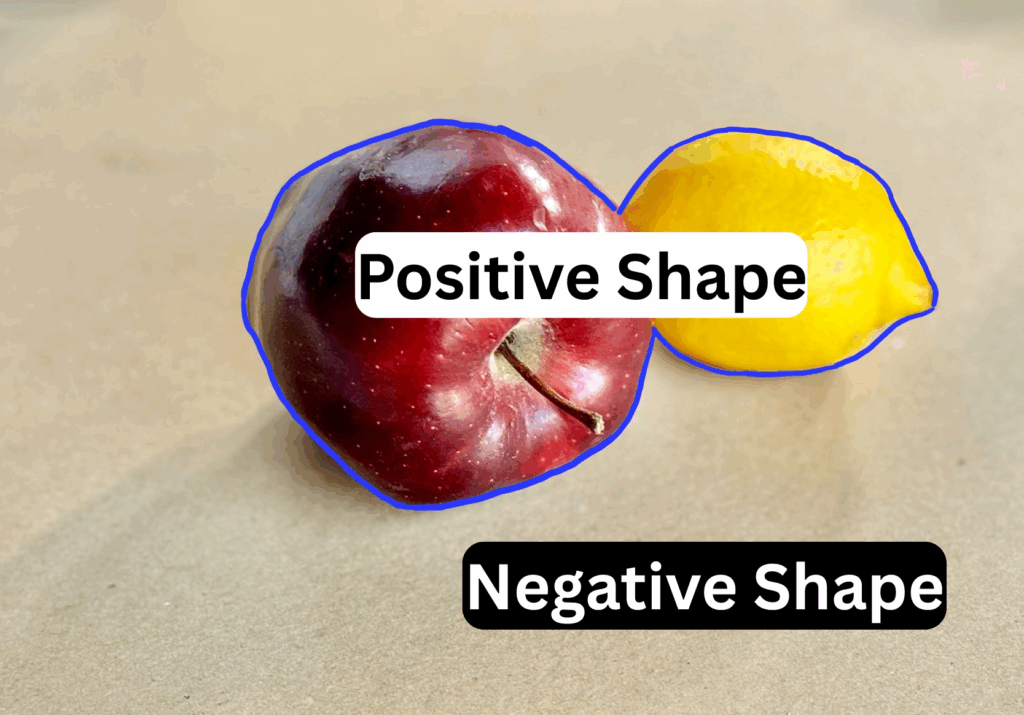

Positive and Negative Shapes

Understanding positive and negative shapes is crucial to mastering composition:

- Positive shape: the main subject

- Negative shape: the space around or between the subjects

Negative shapes play a crucial role in building powerful compositions.

These surrounding spaces are not just empty; they are the key makers of a powerful composition. Paying close attention to these negative areas is just as important (it can be more important in my opinion) as focusing on the main subjects themselves.

When negative shapes are interesting and thoughtfully organized, they bring balance, harmony, and strength to your artwork. In fact, the quality of your negative spaces often determines whether a composition feels dynamic and complete, or awkward and unresolved.

As you explore shape in your own work, challenge yourself to see and shape the spaces in between.

“A good composition isn’t just what you add—it’s also what you leave.”

➤ I’ll dive deeper into this when we explore Composition and figure-ground relationships in a future post—so stay tuned!

Let’s take a closer look at how artists have used positive and negative shapes to create strong visual impact.

Henri Matisse, Anfitrite, 1947. Image courtesy of WikiArt

Kara Walker, Exodus of Confederate from Atlanta, from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), 2005. Image courtesy of WikiArt

Walker’s Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta is a striking example of how positive and negative shapes interact to create visual tension and depth.

Layered Complexity:

The large black silhouette (outer human head) acts as the positive shape against the historical print background. However, within this silhouette, the cut-out inner head becomes a negative shape, revealing fragments of the background. This creates a nested relationship: the black silhouette is both a positive shape (against the print) and a negative space (for the inner head).

Dynamic Composition:

The background print, though partially obscured, functions as a negative shape that frames the central figure. Yet, its details (buildings, figures) also compete for attention, blurring the line between foreground and background.

This artwork can spark deep discussions about how artists manipulate shape to guide the eye and structure the meaning.

Abstraction & the Essence of Shape

Abstraction in art often involves reducing forms to their essential shapes—a process of visual distillation. Artists simplify natural or complex subjects to basic forms in order to:

- Highlight rhythm

- Evoke emotion

- Reveal structure

The degree of abstraction in art can vary greatly—from pure shapes, which are essentially geometric as seen in Malevich’s work, to biomorphic shapes in Gorky’s paintings, to the playful combinations found in Joan Miró’s art, and even to the highly fluid shapes exemplified by Frankenthaler. In each case, artists use shape in increasingly abstract ways, moving further from recognizable objects and toward pure visual expression.

Pure Forms (geometric shapes)

You will find it contradictory to use ‘form’ here. While “pure shapes” could be understood in this context, “pure forms” is the term more directly associated with Malevich’s philosophical and artistic intent in Suprematism.

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition, 1915 – 1916. Courtesy of Tula Regional Museum of Fine Arts, Tula, Russia

Biomorphic Shapes (inspired by living organisms)

Arshile Gorky, The Liver is the Cock’s Comb, 1915. Image courtesy of WikiArt

Combination of All Shapes or Hybrid Shapes

Joan Miró, The Tilled Field, 1923. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Fluid Shapes

Helen Frankenthaler, Moving Day, 1961. Image courtesy of WikiArt

Again, you may hear ‘fluid forms’ when talking about Frankenthaler’s work. This term may refer to the artistic movement or style associated with her work in that era.

All of these are considered nonobjective: they are shapes that do not reference any recognizable objects or suggest any specific subject matter. This freedom from representation allows artists to explore the expressive potential of shape, color, and composition alone.

Conclusion: Why Shape Matters

Shape is a universal visual language—it connects nature, design, architecture, and abstract thought. To study shape is to understand:

- How meaning is constructed visually

- How we perceive space

- How art communicates with clarity and emotion