Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Many students begin drawing without first considering the format. Yet format is not an afterthought—it should be the first decision, even before planning the composition.

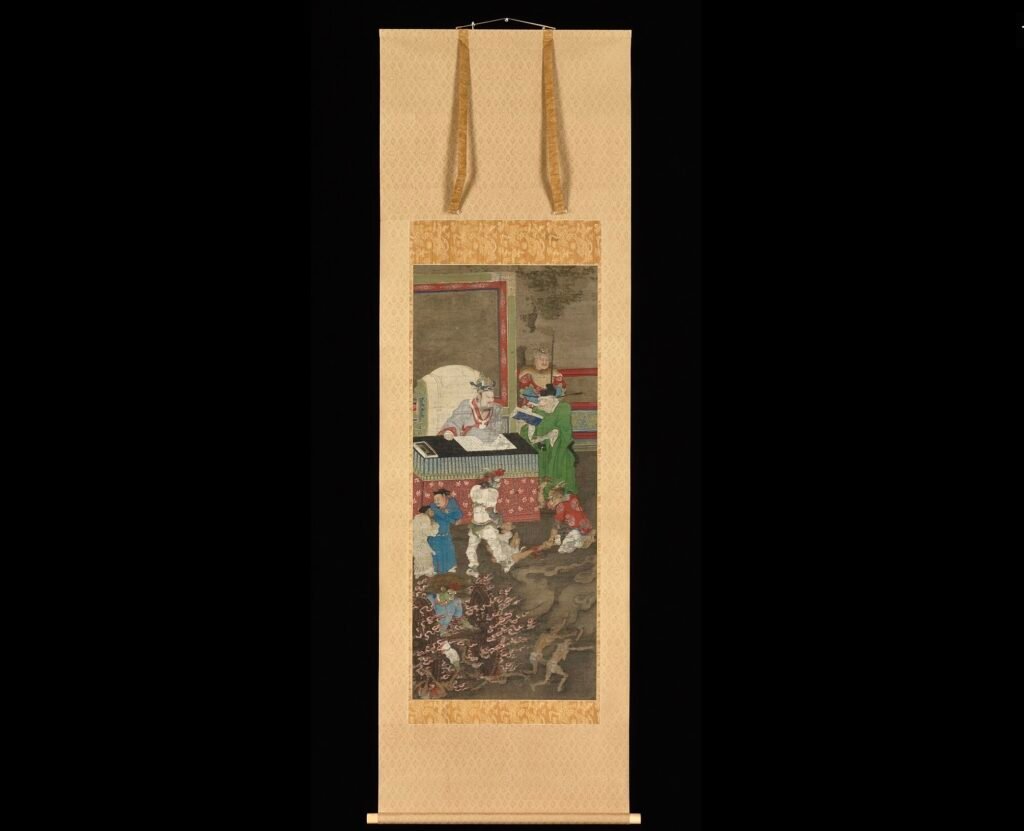

Would a horizontal format best emphasize New York’s towering skyscrapers? Or a vertical one to capture the calm expansive seascape? Likely not.

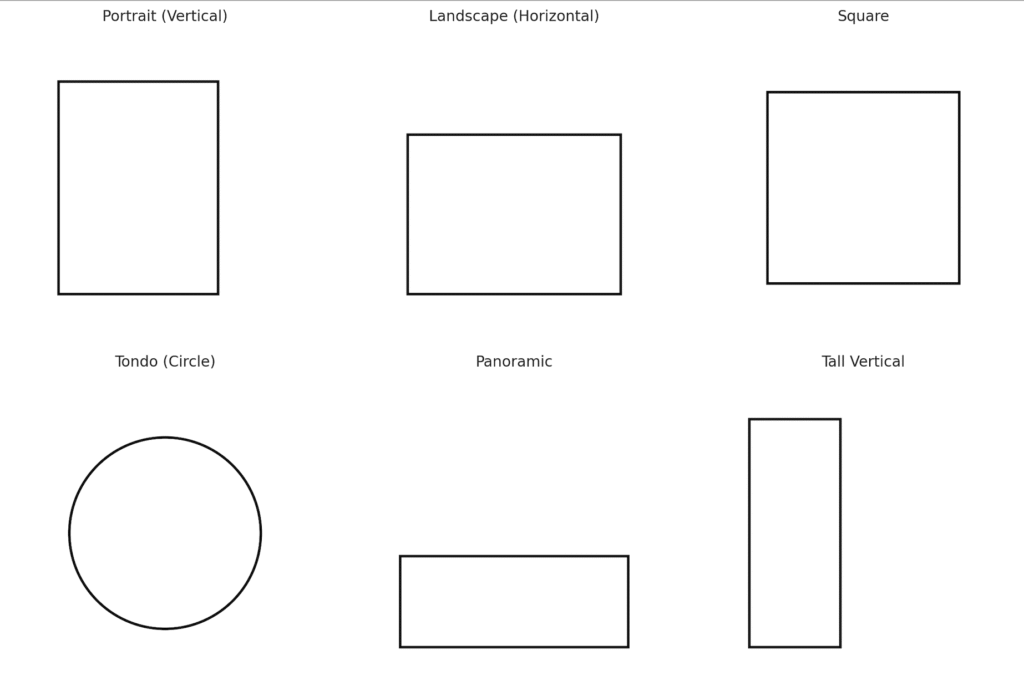

Format—whether vertical, horizontal, square, or panoramic—isn’t just a neutral frame. It is part of the composition itself, and it can make or break the success of a work.

That’s how important it is.

In visual art, format refers to the overall size, shape, orientation, and boundary of an artwork (canvas, paper, panel, screen, etc.) before any compositional decisions are made.

You can explore more about how format is used in modern art through museum resources like Tate.

The mathematical relationship of width to height:

Format = the foundational container: the predetermined outer structure.

Composition = what happens inside—how line, color, shape, space, and other elements are arranged.

Format always comes first: it frames, limits, and inspires the artist’s compositional decisions.

The format powerfully shapes mood and intent:

Format guides the viewer’s expectations and engagement before any mark is made.

While digital cropping tools are convenient, they don’t offer the same experience as using a physical viewfinder. With a smartphone, people often crop images quickly and passively. But with a physical viewfinder, you tend to engage more actively—searching, framing, and observing your surroundings with greater intention.

Using a physical viewfinder helps you pre-visualize your composition. You naturally start to assess the atmosphere, light and shadow, and stylistic possibilities of a scene. Over time, this strengthens your mind’s eye—training you to organize what you see into compelling images. It’s a powerful way to develop visual awareness and compositional instinct.

That said, I don’t discourage using smartphone tools—they’re practical, and most people gravitate toward them. But I encourage students to try both and compare the experience.

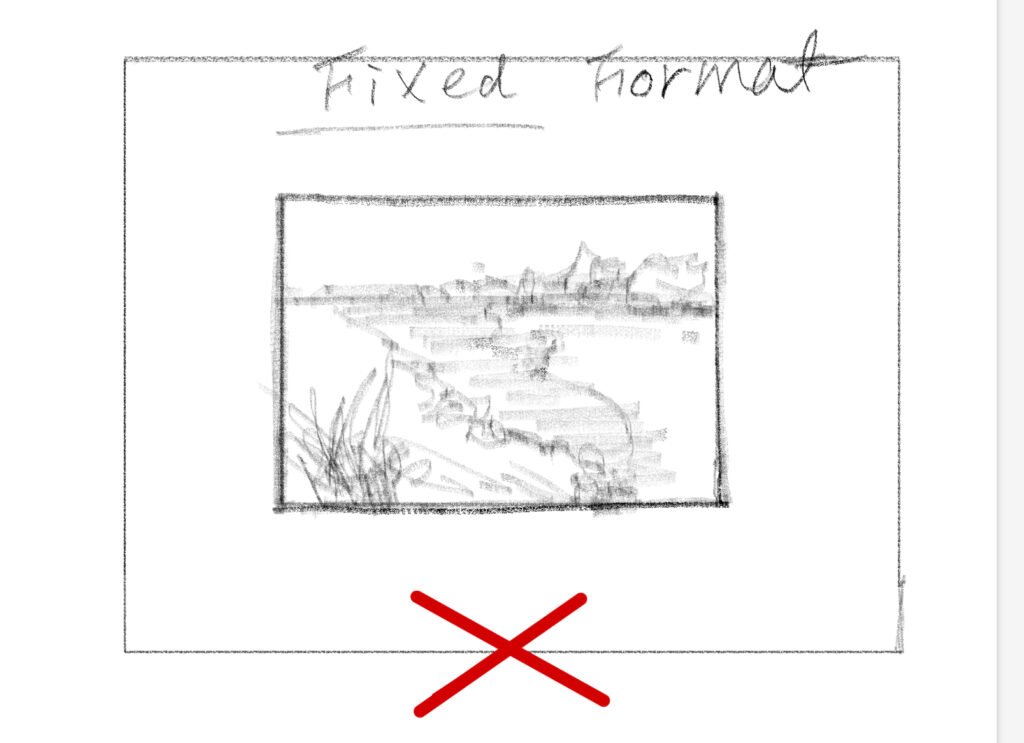

Most viewfinders come in a fixed frame size, which limits your options. I don’t recommend those unless you always work in one specific format.

Instead, I suggest a simple homemade version:

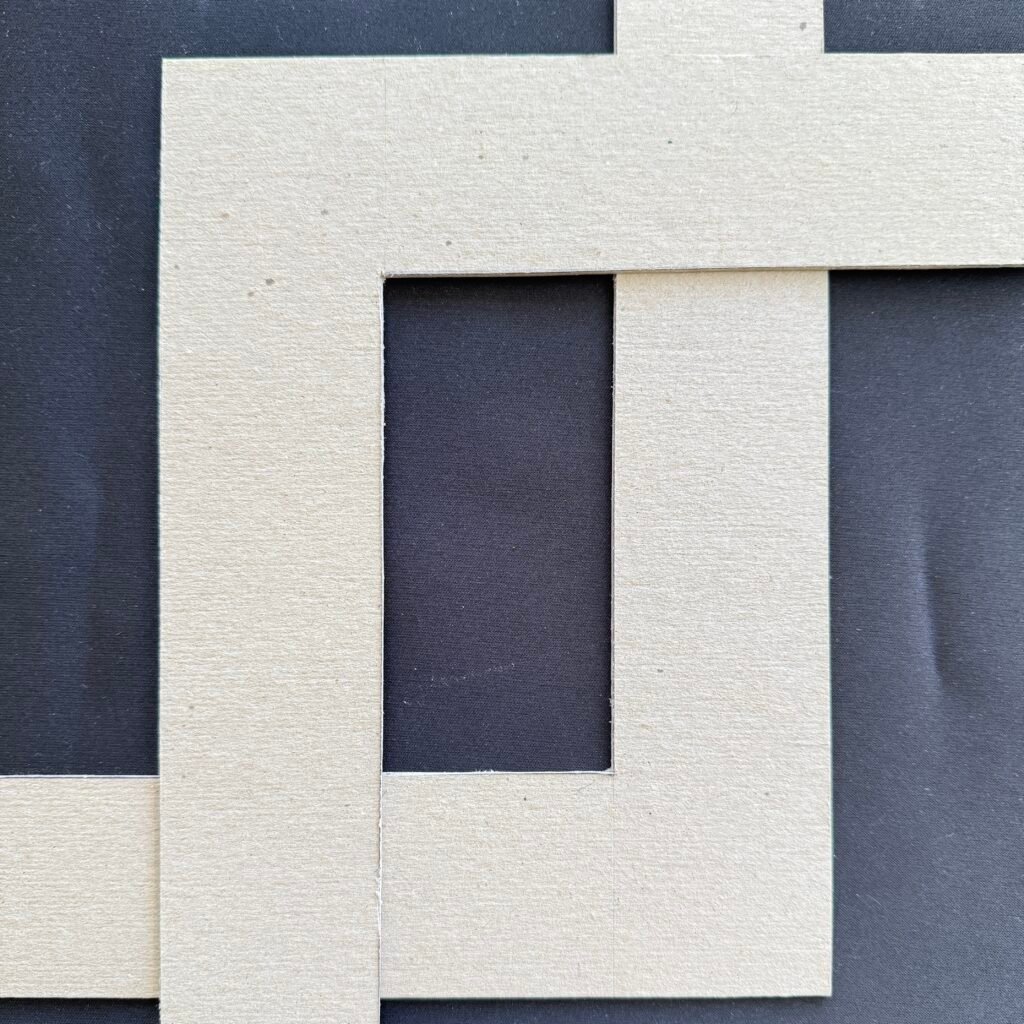

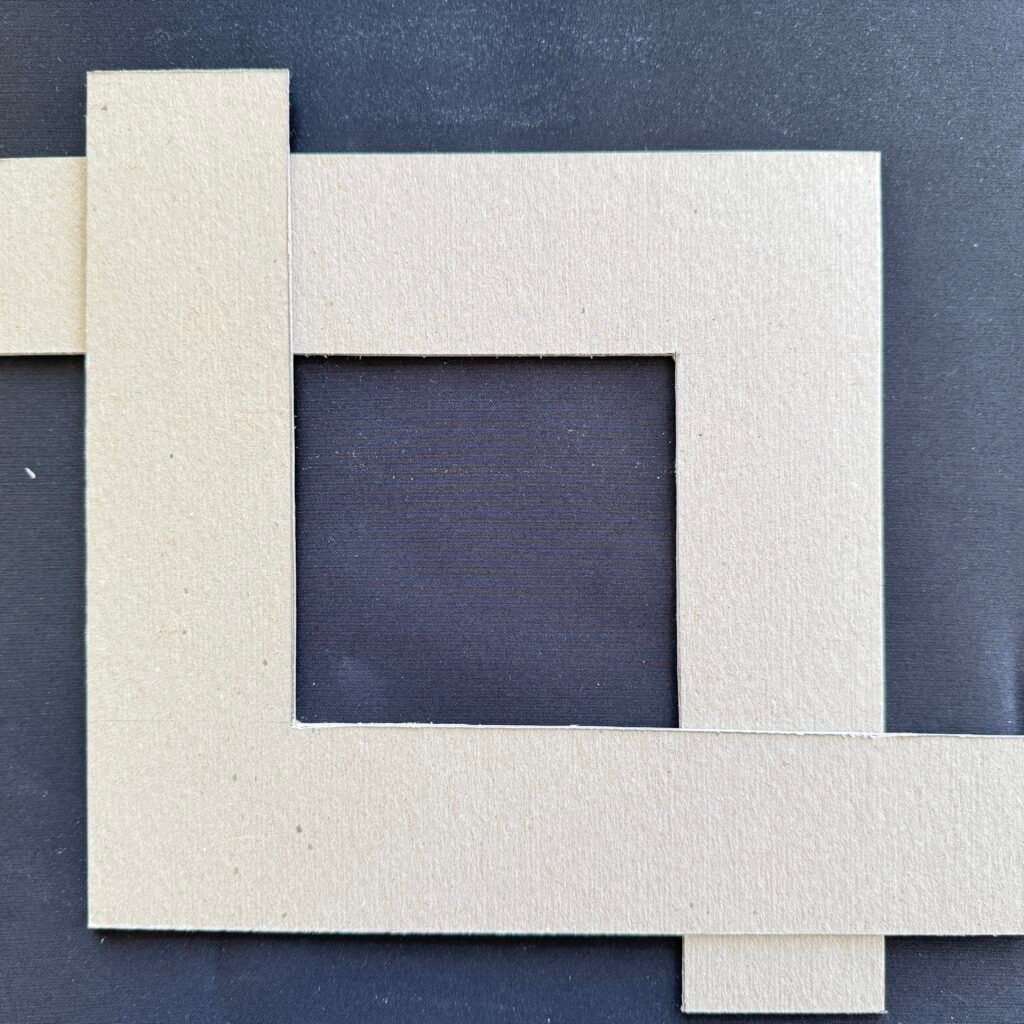

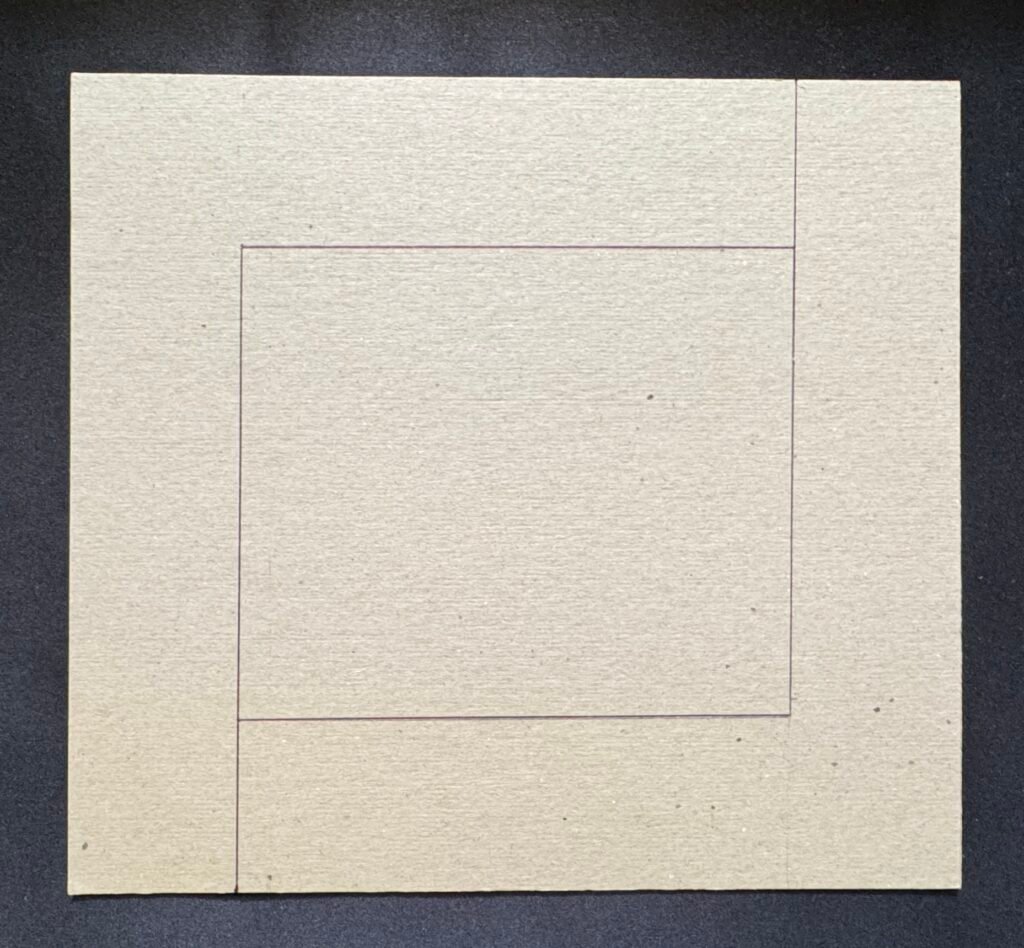

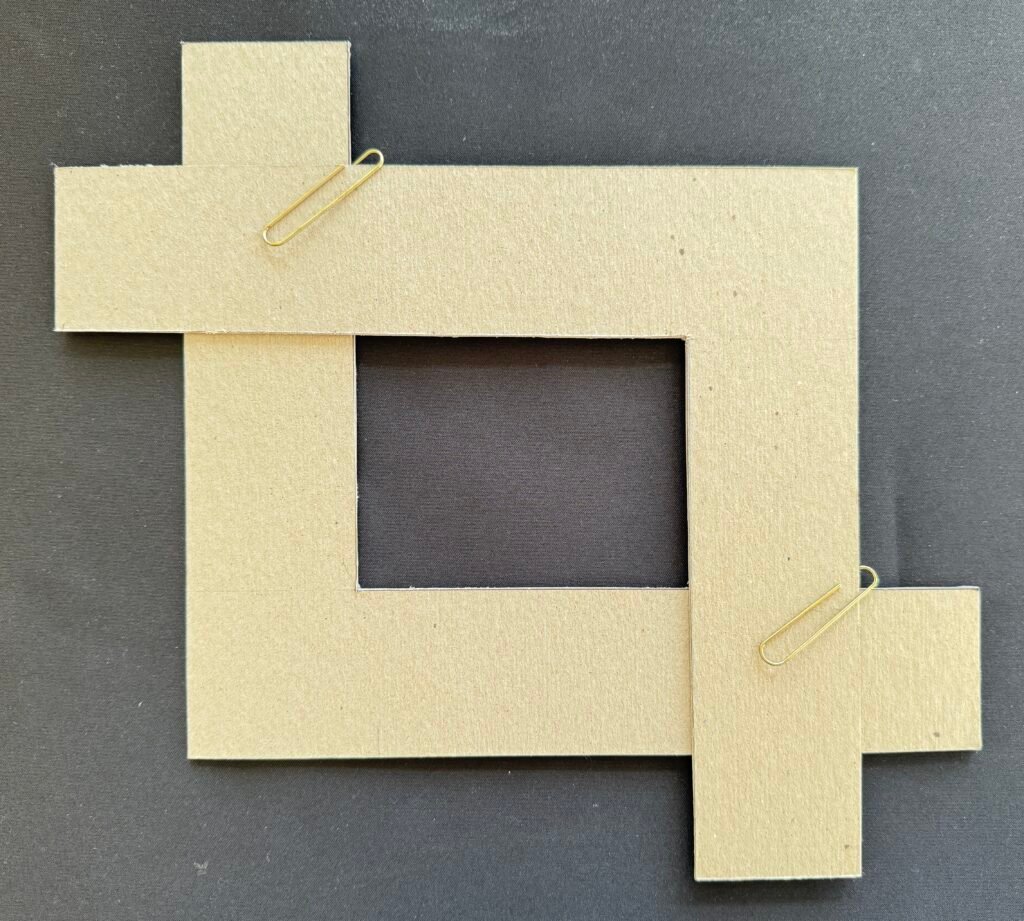

Cut two L-shaped pieces from any stiff, heavyweight paper or cardstock. After exploring different formats, choose the one that works best for your composition. Then, secure the Ls together with two paper clips, like you see here in the images.

This lets you adjust the frame to any format—square, rectangle, vertical, horizontal—so it’s much more versatile for exploring compositions.

The viewfinder shown here measures approximately 8–10 inches on each side and just over 2 inches wide. I made this larger size for a classroom demonstration, but yours doesn’t need to be this big. A smaller version will work just as well for personal use or outdoor sketching.

Here’s a version I found online. I haven’t tried it myself, but it looks pretty handy. If you’d prefer to buy one instead of making your own, this kind of viewfinder could be a good option.

Selecting the right format isn’t just an early technical step—it’s a creative decision that determines how the composition will unfold, how the mood is set, and sometimes even carries symbolic weight.

Careful consideration of format empowers artists to be intentional, shaping not only how the subject is framed but also how the artwork resonates with its environment and with the viewer.