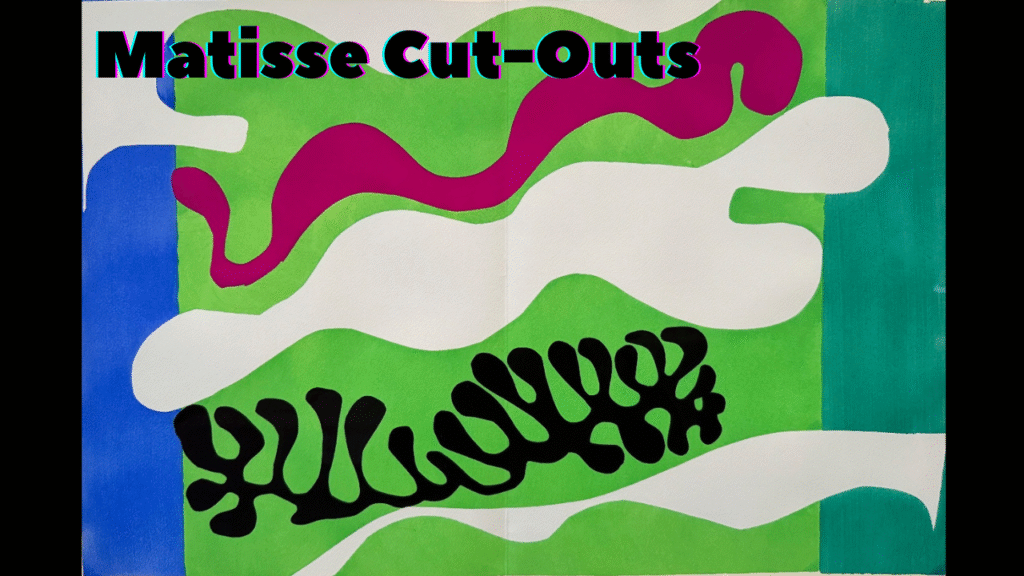

Henri Matisse’s Cut-Outs: A Second Life in Color and Shape

Henri Matisse’s cut-outs are among the most revolutionary achievements of twentieth-century art. Matisse, however, did not originally consider the cut-outs a stand-alone art form until 1941, when a life-threatening cancer surgery left him bedridden and later confined to a wheelchair.

Prior to 1941, he used cut paper primarily as a preparatory tool—for compositional studies, color arrangements, and architectural designs such as his mural for the Barnes Foundation.

Commissioned by Albert C. Barnes, this mural was designed using full-scale cut-paper studies (now lost but documented in photographs and letters). These early experiments mark the beginning of the cut-out techniques Matisse would fully develop more than a decade later.

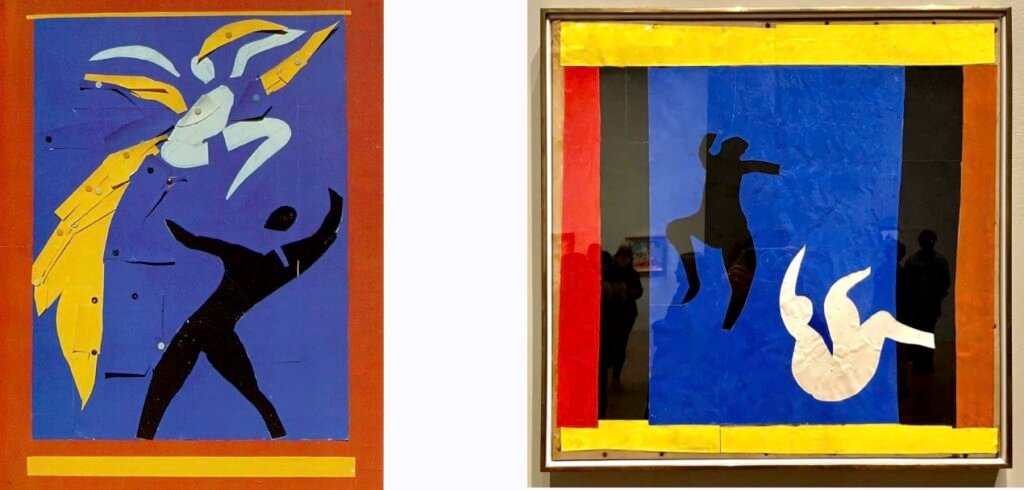

These late-1930s cut-paper studies were preparatory works for the Rouge et Noir and Le Chant. They reveal Matisse’s growing interest in silhouette, movement, and the expressive potential of cut shapes years before his mature cut-out method.

Traditional oil painting became physically taxing, and Matisse turned to cutting painted paper as a more manageable, yet deeply expressive, way to create. He later spoke of this period with gratitude, saying that it felt as though he had entered “a second life.”

Importantly, this shift was not a departure from his previous work. Rather, it represented the culmination of decades of artistic exploration. The cut-outs mark one of the most revolutionary achievements of his career, leading to major late works such as the Jazz portfolio, the designs for the Vence Chapel, and many other iconic compositions.

This post brings together the heart of his cut-out work—how they emerged, how he made them, and why they matter.

1. How Matisse Arrived at the Cut-Outs

Early Life and Breakthrough

Matisse, born in 1869, in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, France, was a pioneer of Fauvism—as seen in The Joy of Life (shown above)—a movement defined by bold saturated colors. His belief was that color could generate form and emotion on its own. He was searching for a way to merge drawing and color into a single unified act.

He once asked his friend, Signac: “In my picture, did you find a perfect balance between the character of the drawing and the character of the painting? To me, they seemed totally different from one another, absolutely contradictory even.”

It was his lifelong search that would culminate decades later in the cut-outs.

The Pursuit of Harmony: Toward Simpler, More Essential Forms

Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, Matisse continued refining his art toward greater simplicity.

1. Influence of Travel

His travels profoundly shaped his imagination:

- Morocco (1912–13): luminous light, geometric patterns, bold contrasts

- Tahiti (1930): tranquil lagoons, silhouettes of plant life, immense quiet

2. The Southern Light of Nice

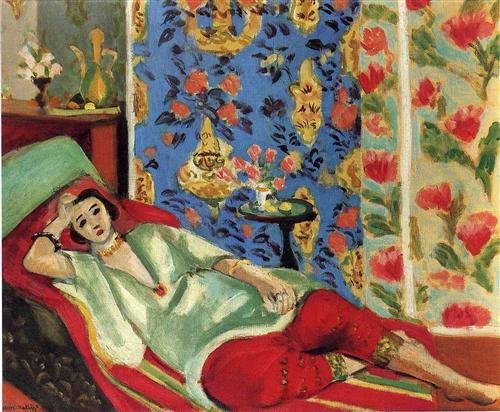

From 1917 onward, Matisse lived in Nice, where Mediterranean light softened his palette but sharpened his understanding of form. The interiors and odalisques of the 1920s reveal a growing interest in:

- Flat patterns

- Silhouette

- Decorative rhythm

- Strong contour

The cut-outs did not appear suddenly—they were quietly forming beneath the surface.

The Road Toward Abstraction: 1930s—A Decade of Reduction

By the 1930s, his work leaned increasingly toward:

- Simplified contours

- Fewer lines

- Clearer shapes

- A growing emphasis on pure color planes

- A return to the founded principles he explored during Fauvism

- A move toward compositions that extended beyond the conventional frame

He later described this goal as ‘a form simplified to its essential character.’

For an excellent visual sequence of Matisse’s working process on Large Reclining Nude (1935), see the National Art School’s study resource here.

Crisis and Reinvention: The “Second Life”

After his 1941 cancer surgery, painting became physically strenuous, and he turned to scissors; what began as a practical adaptation became a radical new medium.

Matisse had used cut paper before for planning murals and decorative schemes, but he now recognized that it could function as a fully autonomous artistic language. With scissors in hand, he began cutting directly into color, creating a new method that synthesized line and color in a single gesture.

2. The Process: From Gouache to Composition

For a discussion of Gouache Painting, please see the earlier post: Gouache vs. Watercolor

For more images and archival materials, see MoMA’s Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs.

Matisse’s technique combined painted paper and precise cutting:

- Studio assistants painted heavyweight paper with gouache—a matte, vibrant medium favored for its intense color.

- Matisse cut freeform shapes directly from these sheets, often without preliminary sketches.

- He arranged pieces on boards or walls, pinning and moving them until achieving the desired balance and rhythm.

- For large-scale works, assistants traced pieces or completed mounting to preserve the final design.

This hands-on process allowed quick adjustment and constant experimentation with proportion, placement, and color interactions.

Compositions grew and shifted like choreography.

3. Essential Works and Their Significance

Jazz series. Image courtesy of WikiArt

What began as bedside compositions grew into monumental, architectural artworks.

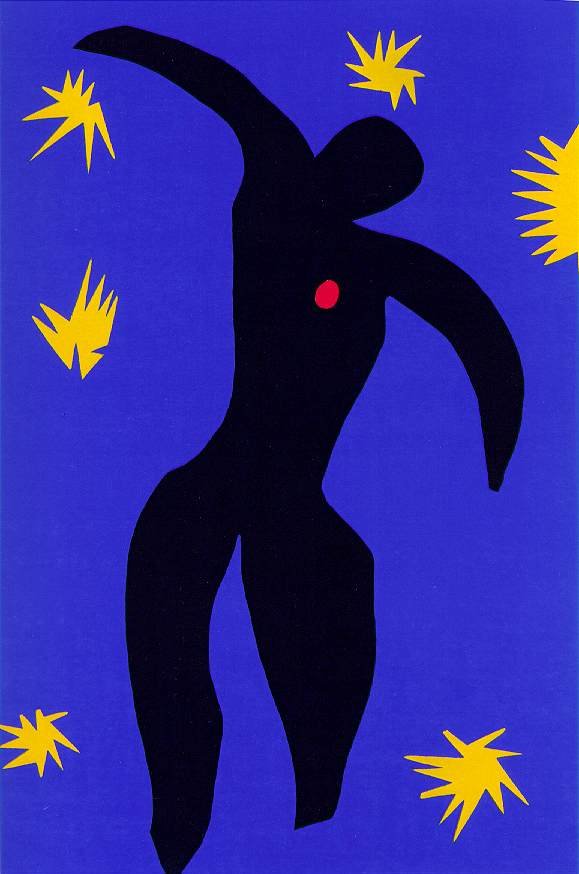

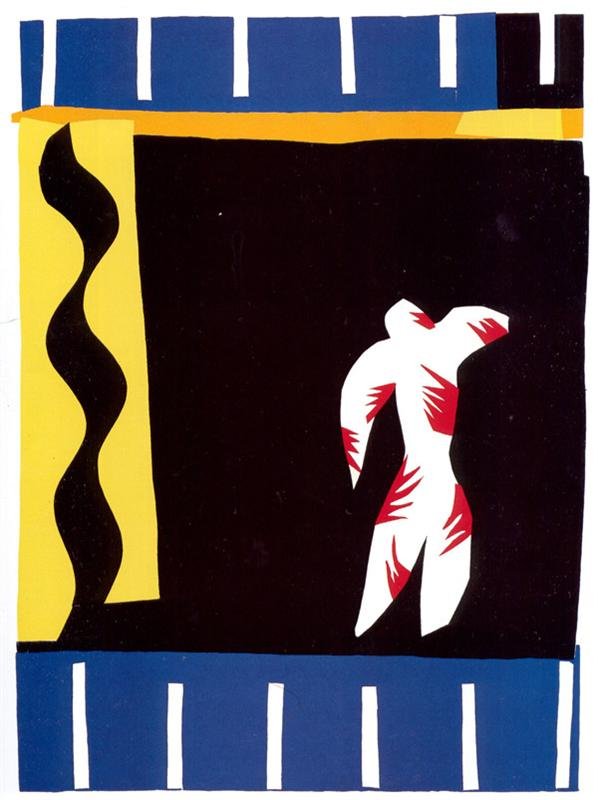

- Jazz Portfolio (1947): Marked the recognition of cut-outs as a masterful standalone medium. Includes iconic works like “Icarus,” which blends myth, emotion, and abstraction.

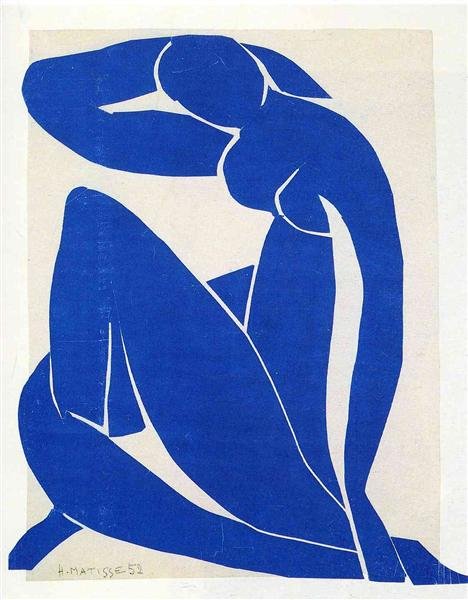

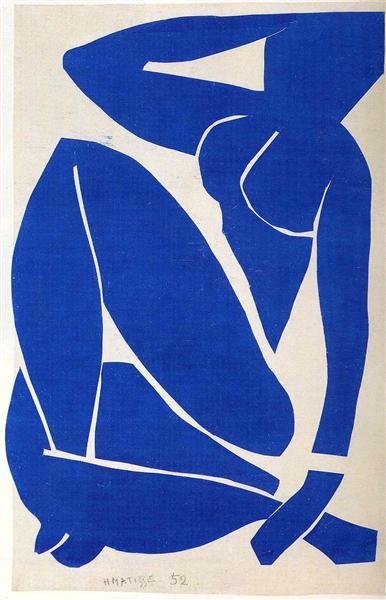

- Blue Nude Series (1952): Four deep blue cut-out figures distill the human form into expressive, simple shapes.

- La Piscine (“The Swimming Pool”)(1952): A monumental room-sized installation, showcasing Matisse’s approach to immersive decoration.

- The Parakeet and the Mermaid: A vast blend of abstract plant, aquatic, and figurative shapes.

- Vence Chapel (1948–1951): All major designs for the spiritual masterpiece—stained glass, murals, vestments—all designed through as cut-outs.

4. Why Matisse’s Cut-Outs Matter

Henri Matisse’s cut-outs transformed modern art by redefining how artists think about shape, color, composition, and the processes behind visual decision-making. They were the culmination of a lifetime spent refining color, line, balance, and emotion.

Spontaneity, Directness, and Emotion

Matisse often said, “The problem for me is to strike a balance between my drawing, the colors, and my feeling.”

The cut-outs finally enabled that balance. They gave him a way to work intuitively, bypassing the separation between line drawing and painting.

He described the process this way:

“The paper cut-out enables me to draw directly into color—instead of drawing the contour and filling it in.”

This immediacy allowed him to translate emotion into form with unprecedented clarity. The Clown (1943) embodies this fusion.

Its dynamic silhouette appears simultaneously playful and charged, suggesting both the joy and danger embedded in performance. The work can be read as a reflection on the dual nature of life—its exuberance and its underlying fragility.

Cutting into Color: Uniting Line and Color

His cut-outs allowed him to merge the two artistic languages he mastered over decades:

- Color: As a fauvist and throughout his “Nice period” of the 1920s, he pursued what he called “construction by means of color,” using bold, saturated hues.

- Line: As a master draftsman, he described his lines as “the purest and most direct translation of my emotion.”

By “drawing with scissors,” Matisse fused these two impulses—infusing shape with both color and contour in a single gesture.

In the cut-outs, shape and color become inseparable. Together, they form a unified visual language that sits at the heart of Matisse’s late style and stands as one of the most influential innovations in modern art.

Gateway to Abstraction

This merging of form and color opened a gateway to modern abstraction. The act of cutting teaches composition and simplification in a direct, hands-on way, encouraging an understanding of relationships between shapes rather than objects.

The Blue Nudes demonstrate that abstraction and figuration are not opposites; in Matisse’s hands, they become fully reconciled.

Embracing Simplification

In series such as Jazz and the Blue Nude cut-outs, Matisse reduced visual complexity to a few powerful shapes.This simplification heightens impact: with only minimal elements, he builds compositions full of dynamism, emotion, and clarity.

Positive and Negative Space

For a deeper discussion of positive and negative space, please see the earlier post: Positive and Negative Shapes: Essential Guide

In traditional painting, space is often constructed through layering—background settles behind foreground.

Matisse’s cut-outs fundamentally shift how we understand space:

- Shape and background are created simultaneously.

- The gap becomes as important as the form.

- Figure and ground can reverse roles.

Matisse’s cut-outs teach something fundamental:

Space is not what you fill—it’s what you activate.

Rhythm, Movement, and Scale

Large expanses of crisp color and repeated motifs create rhythmic patterns that engage the viewer physically and visually.

The interplay between positive and negative shapes intensifies this rhythm, producing compositions that feel musical, architectural, and immersive.

Chance and Intention

Cut-outs invite serendipity. One of the most compelling aspects of the cut-outs is their interplay between deliberate design and spontaneous discovery:

- A discarded scrap becomes the perfect shape.

- An accidental angle generates a new rhythm.

- Unrelated pieces find harmony when placed together.

Temporality and Assembly

Painting is continuous—each stroke arises from the last.

Cut-outs, by contrast, assemble pieces from different moments, moods, or contexts.

This gives the works a layered temporality, a sense that time itself is part of the composition.

Why Study Matisse’s Cut-Outs?

Artistic Innovation & Reinvention

Matisse’s cut-outs dissolved the boundaries between illustration, collage, sculpture, and design—works that feel accessible and playful, yet remain deeply rigorous in structure and intention.

They also remind us that breakthrough ideas often emerge from limitation; what began as a physical constraint late in his life became the catalyst for one of his most innovative artistic periods.

Bridging Disciplines

Matisse’s method influenced an astonishing range of fields, from painting and printmaking to textiles, design, and large-scale installation art. Such interdisciplinary echoes reveal that the cut-outs were not simply a method, but a new way of seeing—one that reframes how shape, space, and experience can intersect.

Joy, Playfulness, and Discovery

The cut-outs celebrate spontaneity, chance, and the poetry of pure form. They radiate a freedom that encourages artists of all levels to experiment, to discover, and to trust intuition.

A Way of Seeing

The cut-out is more than a technique; it is a philosophy of making—a way of seeing, composing, and engaging with the unknown. It invites both intentional design and serendipity, offering a balance between control and openness.

Closing Thoughts

Matisse’s cut-outs remind us that creativity can remain vibrant, curious, and full of possibility at any stage of life. I hope this exploration encourages you to experiment with shapes, color, and intuition in your own work—embracing both the clarity of intention and the joy of discovery.

Please click the image below to watch the YouTube content.