CY TWOMBLY: ON LINES, DOODLING, SCRIBBLING, AND MARK MAKING

Post Image Above: “Bacchus” – Iron curtain of the Vienna State Opera. Artwork by Cy Twombly, photo by museum in progress. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

What to expect in my blog post: Please check Artists in Culture & History

“Untitled”, 1954 by Cy Twombly. Image via WikiArt

We all have experienced doodling and scribbling without thinking, letting our

unconscious take over. As a student, my textbooks’ margins were filled with doodles, and the notepads by the phone were covered with unrecognizable

drawings—connecting dots and shapes, turning coffee stains into imagined creatures.

These spontaneous marks may seem insignificant, yet they reflect something deeply human: the urge to create instinctively, without conscious effort.

In this way, we all harbor a bit of Cy Twombly within us. Twombly, a pioneering artist of

the 20th century, elevated these instinctive scrawls into a sophisticated artistic

language, blurring the boundaries between drawing, writing, and painting. His works,

often filled with complex layered paints, writings, marks, drips, and scribbled gestures,

captured not just the act of mark-making but also the raw emotion and historical depth

embedded in the process.

Although Twombly’s work is often associated with spontaneous, free-flowing gestures,

his approach was not purely rooted in automatism—the Surrealist technique of allowing

the subconscious to dictate the hand’s movement. While he was exposed to

automatism at Black Mountain College, where he studied under artists like Robert

Motherwell, it did not define his entire artistic philosophy. Instead, Twombly’s gestures

were often deliberate yet unrestrained, influenced by a deep engagement with classical

history, mythology, and poetry. His lines, scribbles, and marks are not simply impulsive

expressions but a refined visual language that bridges historical references with raw,

contemporary abstraction.

Encountering Twombly for the First Time

When I first saw Cy Twombly’s work in a museum, I was still a young student beginning

my journey in art. The experience was nothing short of shocking. At first, I wondered:

How could scribbling or doodling be considered art? They reminded me of the marks I

had made absentmindedly on scraps of paper–marks that always ended up in the trash.

Why were these expressive, seemingly random marks framed, celebrated, and studied?

But my confusion quickly gave way to something deeper. The images in textbooks had

never prepared me for the monumentality and energy of Twombly’s large-scale works.

Seeing them in person, I felt their sheer physicality—as though he had moved across

the canvas with his whole body, letting momentum and emotion guide his hand. His

marks had speed, movement, and rhythm. Though his paintings were

non-representational, they felt alive.

lll Notes from Salalah, (Note ll), 1968 by Cy Twombly. Image via WikiArt

The Language of Emotion through Marks

Twombly’s paintings are more than abstract gestures; they are visualized human

emotions. The drips of red paint radiate intensity, anger or passion, while his repeated

loops and erratic scratches convey a sense of compulsion. Layers of paint, interwoven

with the interplay between writing and mark-making, evoke a sense of memory and

history. Twombly’s art speaks to these everyday marks and elevates them into

something profound—a testament to what it means to be human.

Twombly’s Inspiration and Techniques

Cy Twombly (1928–2011) was an American artist whose work defied easy

categorization. His art existed at the intersection of Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism,

and Conceptual Art, yet remained distinctly his own. His signature

scribbles—sometimes resembling calligraphy, other times graffiti—along with loops, and

gestural marks were not mere accidents; they were rooted in a deep engagement with

history, mythology, literature, and human emotion.

Leda and the Swan, 1962 by Cy Twombly. Image via WikiArt

Classical Influences: Twombly often drew inspiration from ancient mythology and

poetry. His move to Italy in 1957 significantly influenced his work, as he began creating energetic artworks inspired by Roman and Italian mythology, history, and art. For example, his painting Leda and the Swan (1962) reimagines the Greek myth where Zeus transforms into a swan to seduce Leda.

Rather than depicting the scene literally, Twombly used chaotic marks- drips, smudges, and scratches- to convey power, desire,

violence, and transformation in his implicit language.

Classical Influence:

Twombly often drew inspiration from ancient mythology and

poetry. His move to Italy in 1957 significantly influenced his work, as he began creating

energetic artworks inspired by Roman and Italian mythology, history, and art. For

example, his painting Leda and the Swan (1962) reimagines the Greek myth where

Zeus transforms into a swan to seduce Leda. Rather than depicting the scene literally,

Twombly used chaotic marks-drips, smudges, and scratches-to convey power, desire,

violence and transformation in his implicit language.

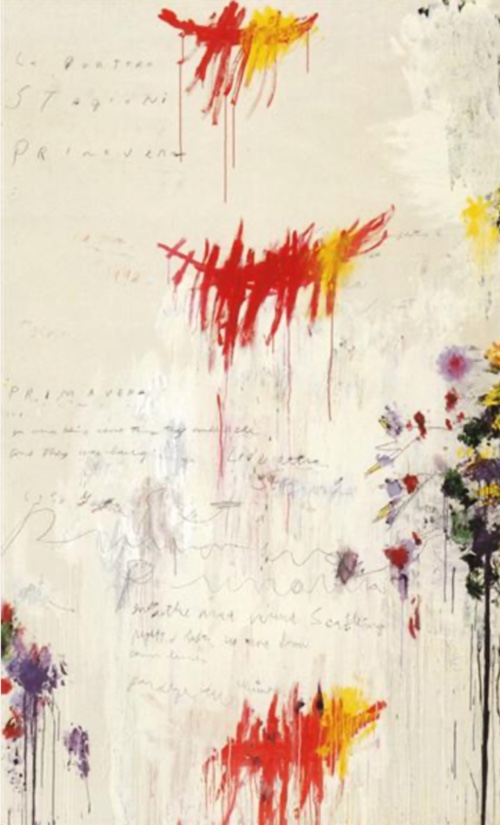

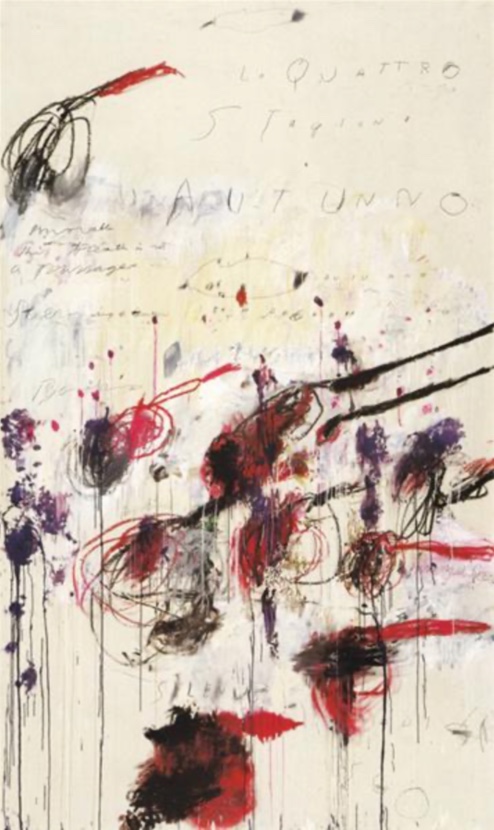

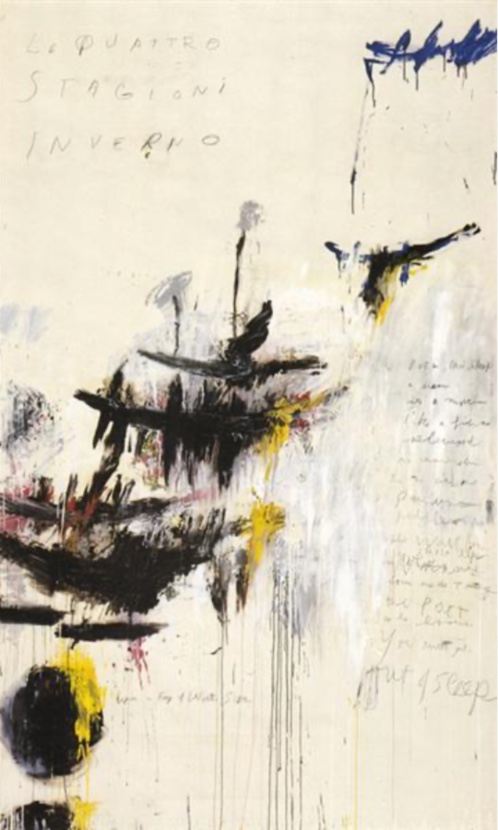

Quattro Stagioni (Four Seasons) series (1993-1994):

Quattro Stagioni l (The Four Seasons: Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter, 1993-1994). Images via WikiArt

It represents the four seasons within the ongoing cycle of life, a theme frequently explored in Classical and Renaissance art that Twombly admired. This series might recall the concept of the

“Four Gentlemen” in Asian ink painting, where each seasonal plant represents the

essence of a season and artistic mastery. In “Primavera” (Spring), Twombly applies

bright red and yellow paint layered over lighter whites to suggest the vitality of spring’s

renewal. His paintings often retain ghost-like traces of past writings, with layers of thin

paint partially concealing and revealing information, creating a palimpsest effect that

adds depth and history to his work.

Visual Poetry:

The Rose (ll),2008 by Cy Twombly. Image via WikiArt

Twombly’s works often include fragments of text—quotes from poets like

Rainer Maria Rilke or Stéphane Mallarmé—blurring the line between visual art and

literature. His paintings become a form of visual poetry, where words and marks coexist

to evoke layered meanings.

The image above is one of The “Rose” series (2008): These paintings feature passages from Rilke’s rose-themed lyrics, exploring the tension between words and images.

Mediums and Mark-Making Techniques

Mediums and Tools: Twombly’s artistic range extended across multiple mediums, each contributing to his unique visual language:

- Oil-based house paint for fluid strokes

- Wax crayon & pencil for writing and mark-making

- Tools & Everyday items such as squeezes, broom handles, brushes, and dried flowers to create unexpected textures

- Fingers

- Plaster on wood for sculptural texture

- Collage for layered storytelling

- Photos

Influences and Artistic Philosophy

Cy Twombly’s artistic journey was shaped by a diverse array of influences. He drew inspiration from prominent Abstract Expressionists like Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, and Robert Motherwell, whose works helped him transition from figurative to abstract art. His close friendship with Robert Rauschenberg also played a significant role in his artistic development, as both artists explored new frontiers in post-war American art.

Twombly’s move to Italy in the late 1950s further enriched his artistic vision. He became deeply fascinated with classical mythology, poetry, and the rich cultural heritage of the Mediterranean. This fascination is evident in works like the “Untitled (Bacchus)” series, where Twombly used paint brushes attached to long sticks to create dynamic, expressive marks. These gestures echoed the primal energy of ancient rituals and allowed him to distance himself from direct conscious control, fostering a more spontaneous and intuitive creative process.

Influence on Future Generations

Twombly’s unique blend of abstract expressionism, graffiti-like marks, and poetic references has had a profound impact on subsequent generations of artists. His work influenced notable figures such as Anselm Kiefer, Julie Mehretu, Francesco Clemente, Julian Schnabel, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, along with Contemporary Calligraphy and Graffiti Artists. These artists, among others, have been inspired by Twombly’s ability to merge high and low cultural references, creating a new language without the boundaries between art and language that is both personal and universally relatable.

Final Thoughts: The Power of Lines and Marks

Cy Twombly’s art challenges us to reconsider what constitutes artistic expression. His lines, scribbles, and marks are not merely aesthetic choices; they are acts of communication—gestures that construct form, suggest movement, and evoke emotion. In their rawness lies their universality: they speak a language we all understand but cannot easily articulate.

Looking back on my own discarded doodles from childhood or idle moments by the phone, I now see them differently. What if, hidden within them, there was an unconscious masterpiece?

*Special Note:

The recently concluded exhibition at Gagosian Gallery, NY, featured an extensive selection of Cy Twombly’s artworks, including several pieces never before displayed publicly. You can explore these works further by visiting the gallery’s website or viewing their exhibition video. Gagosian has hosted numerous exhibitions of Twombly’s art, reflecting the longstanding and close relationship between the artist and gallery founder, Larry Gagosian.

Making It Personal: Responding to Twombly through Your Own Marks

Inspired by Twombly, I decided to explore what mark-making meant to me. Without trying to replicate his paintings, I simply let my hand move freely across the page, using charcoal, wax crayon, graphite, tree branches, and ink. I scribbled, layered, erased, dripped, and scratched. I wasn’t trying to “draw” anything but focusing on the process. They were experiences in mark-making and gesture. I was searching for emotion in movement.

What emerged was not a polished artwork but a visual memory—a layered surface filled with tension, rhythm, and peace. I realized that what drew me to Twombly wasn’t just the history or grandeur of the references but the deep honesty in his marks.

Try It: A Twombly-Inspired Mark-Making Exercise

Materials:

- Large paper (or even a brown grocery bag)

- Charcoal, crayons, ink, writing tools, or paint

- A stick, your fingers, or a brush

- Non-traditional art supplies like tree branches/twigs or tools like a broom

- Optional: a quote or line of poetry

Steps:

- Choose a word, memory, or mood. Don’t draw it. Instead, respond to it with marks.

- Work fast. Scribble. Slow down. Pause. Drip. Smudge.

- Layer your marks, then erase over them or cover them with white paint or gesso. Let the past linger beneath the surface.

- Add a fragment of text, scrawled quickly. Let it disappear under layers. Let it live like a whisper.

This is what it means to engage with Twombly—not to copy, but to feel your way through the process.