Georgia O’Keeffe: Where Earth Meets Sky

Post Image: Georgia O’Keeffe, Hollyhock Pink with Pedernal, Oil on Canvas, 1937. Image Courtesy of WikiArt

Exploring the Artist’s World through My New Mexico Journey

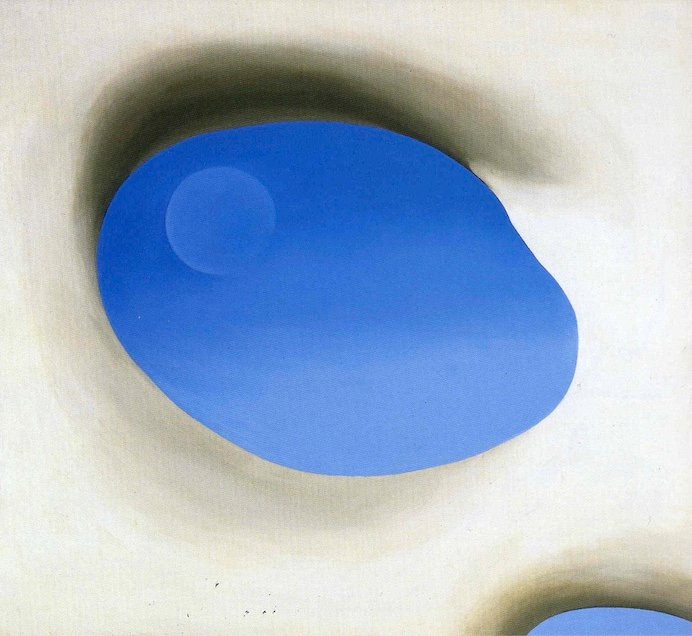

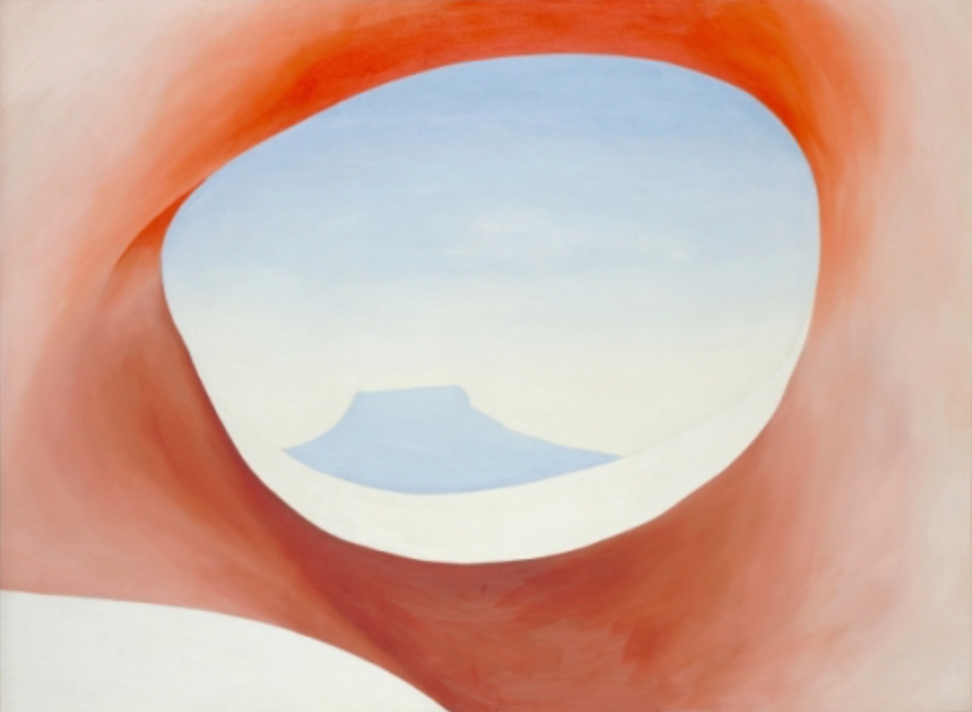

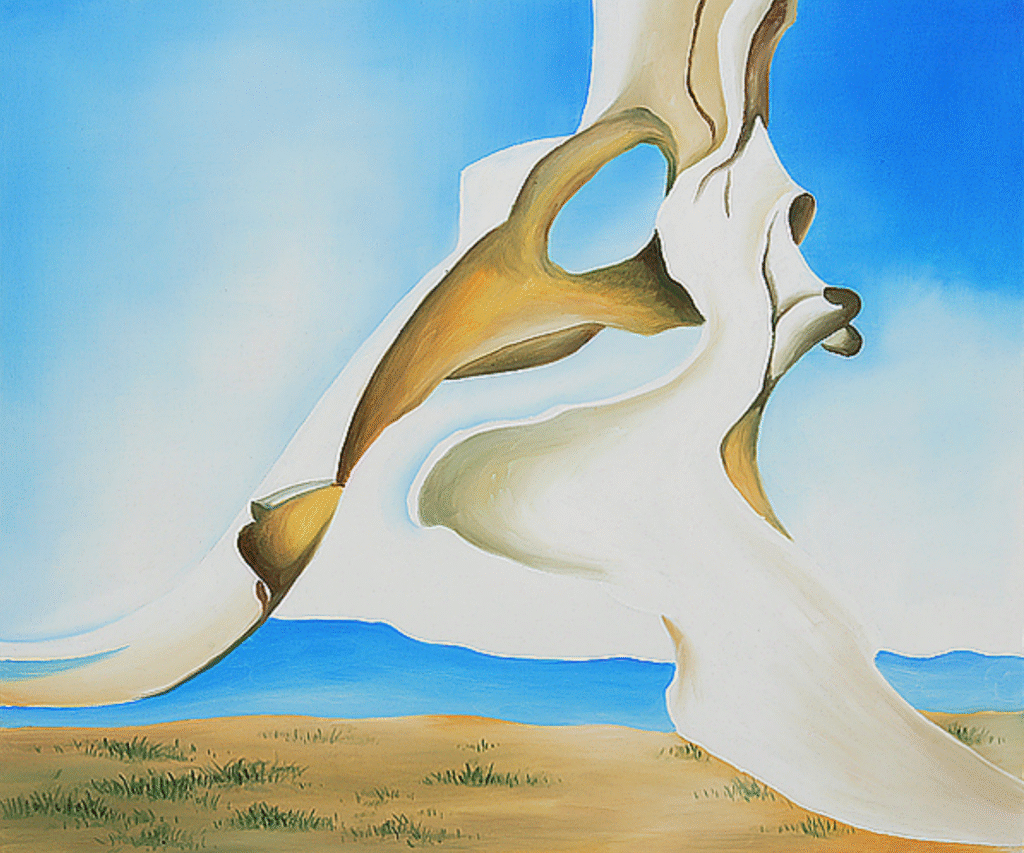

Post Image: Georgia O’Keeffe, Pelvis lV, Oil on Masonite, 1944. Image courtesy of WikiArt

Georgia O’Keeffe, My Backyard, Oil on Canvas, 1937. Courtesy of New Orleans Museum of Art

Georgia O’Keeffe: The Mother of American Modernism

Georgia O’Keeffe during her time at the University of Virginia

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) was a pioneering American artist whose work blurred the boundaries between abstraction and representation. Best known for her large-scale flower paintings, stark desert landscapes, and abstracted natural forms, O’Keeffe forged a deeply personal vision of the world. Her art captures both the monumental and the intimate—inviting us to look closer, feel deeper, and rethink the ordinary.

Raised on a dairy farm in rural Wisconsin, O’Keeffe’s early connection to nature would remain a lifelong source of inspiration. She studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Art Students League of New York, and Teachers College at Columbia University, where she trained as an art teacher.

O’Keeffe first captured the attention of the New York art world in 1916, when her radically abstract charcoal drawings were exhibited at Alfred Stieglitz’s influential 291 gallery. This exhibition not only launched her career but also introduced her to Stieglitz himself, the renowned photographer who would become her husband and lifelong supporter.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Red Canna, 1923. Courtesy of Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Georgia O’Keeffe, Series 1, No. 8, 1919. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. © Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus

Vision & Influence: O’Keeffe’s Artistic Evolution

A pivotal moment in O’Keeffe’s artistic development came when she encountered the teachings of Arthur Wesley Dow, who encouraged creative expression through composition and form rather than strict imitation—a philosophy that profoundly shaped her style. She was also influenced by movements like Precisionism and Cubism, which can be seen in her bold use of color and simplified forms.

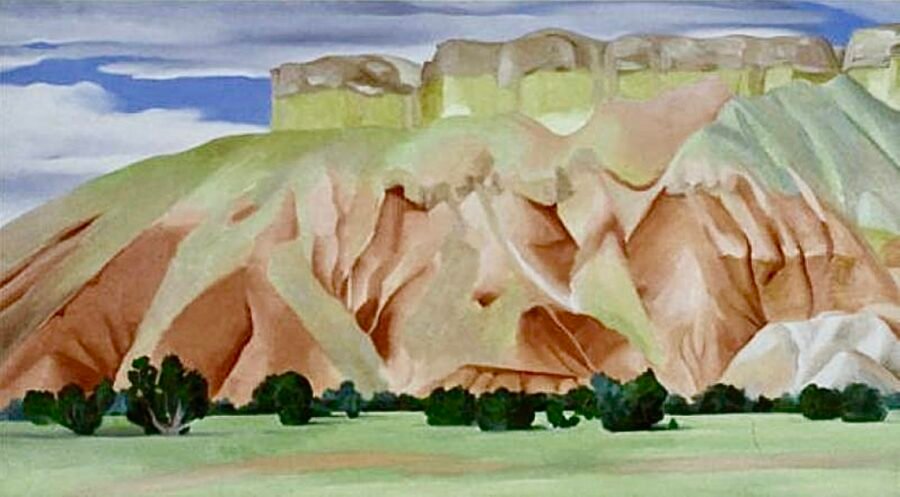

Her move to New Mexico in 1949 marked a turning point, inspiring the landscapes and motifs that define her most iconic works. O’Keeffe’s innovative approach to color, form, and subject matter helped redefine American art. Her ability to capture the emotional resonance of landscapes and objects continues to inspire artists and captivate audiences around the world.

As O’Keeffe once said, “Colors and shapes make a more definite statement than words.”

Why I Traveled to New Mexico

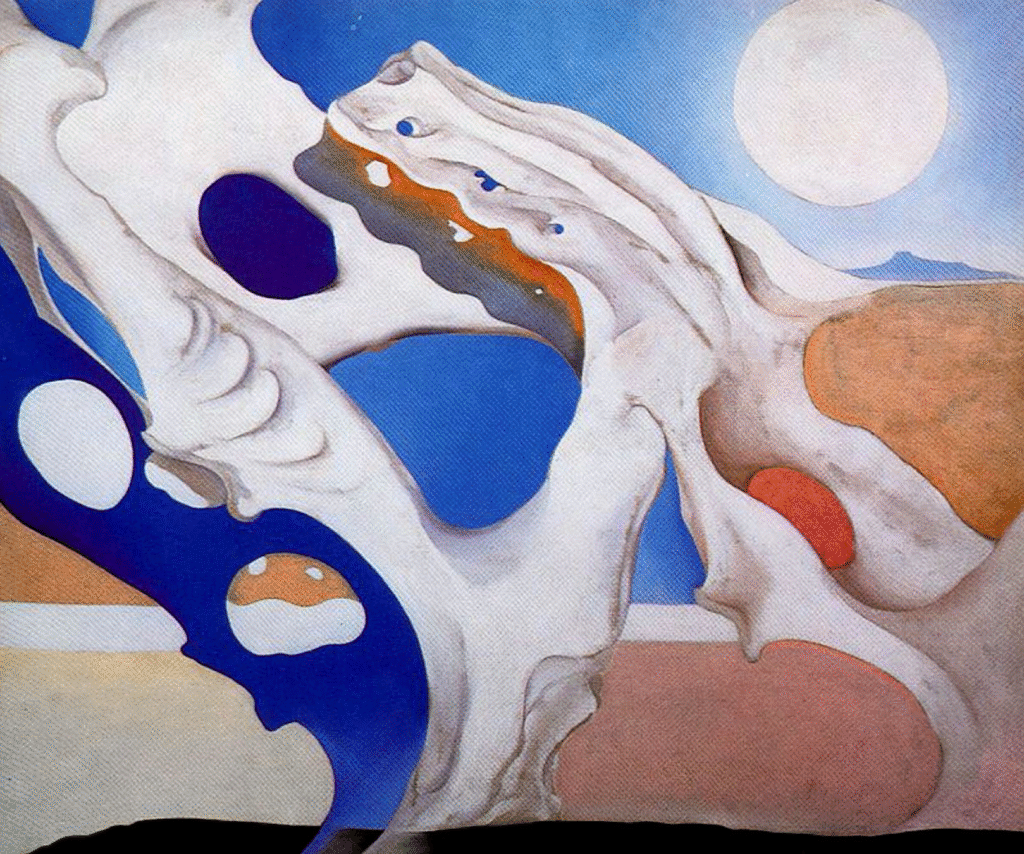

Georgia O’Keeffe, Shadow with Pelvis and Moon, Oil on canvas, 1943. Private Collection via WikiArt

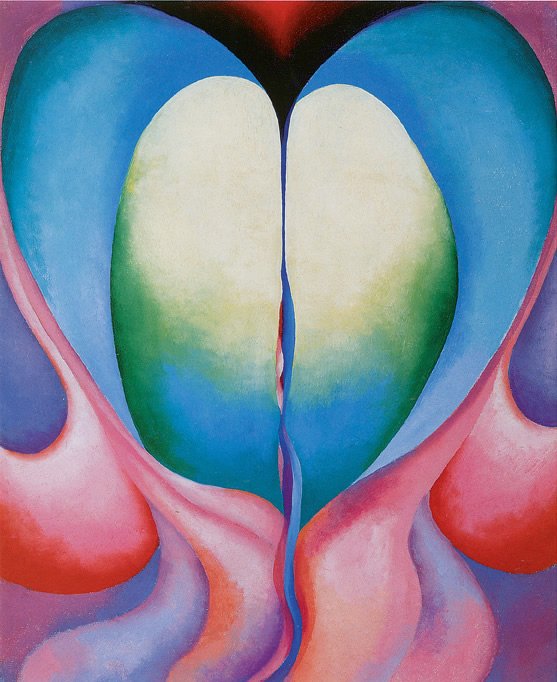

Among O’Keeffe’s vast body of work, I have always been captivated by her paintings of the blue sky glimpsed through the hollowed forms of animal skulls. These haunting images have long stirred my curiosity: Why was she drawn to bones? What did she discover in the voids of a pelvis or skull held up against the endless New Mexico sky? What was she hoping to communicate through these surreal juxtapositions?

Georgia O’Keeffe, Pedernal – From the Ranch l, Oil on canvas, 1956. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Cowles

Her dramatic landscapes and the evocative settings of her homes in Abiquiú and Ghost Ranch raised even more questions for me: What was it about these places that so deeply inspired her? What kind of environment shaped her choices and her vision? Why did she choose to settle in New Mexico, and how did its landscape become such a vital part of her art?

As someone who loves to trace the roots of artistic inspiration, I rarely stop at simply admiring an artwork. Instead, I’m compelled to explore the artist’s environment, influences, and personal history. This quest for deeper understanding led me to finally embark on my long-postponed journey to New Mexico—to walk in O’Keeffe’s footsteps and connect my own experience to hers.

This post focuses on those iconic locations and the specific body of work O’Keeffe created during her time in New Mexico. I look forward to exploring more facets of her art in future blog posts and in my “Follow Along” series on YouTube.

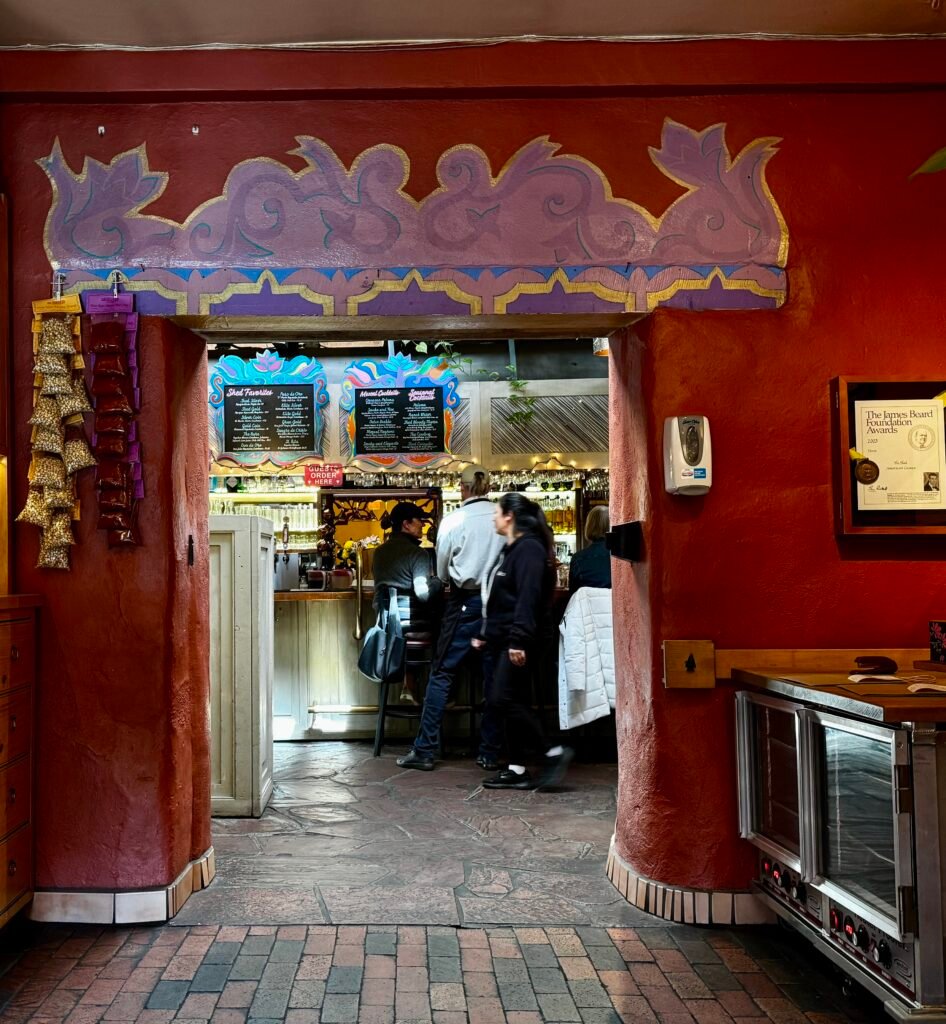

The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe

Santa Fe is a city steeped in culture—a vibrant tapestry woven from Native American, Spanish, and American influences. Its dynamic art scene, rich history, and renowned cuisine make it a joy to explore.

Downtown, Santa Fe

Nestled in the heart of this creative city is the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, offering a comprehensive look at the artist’s life and work. With a rotating selection of her art, each visit promises a fresh perspective.

John Phelan, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe NM, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

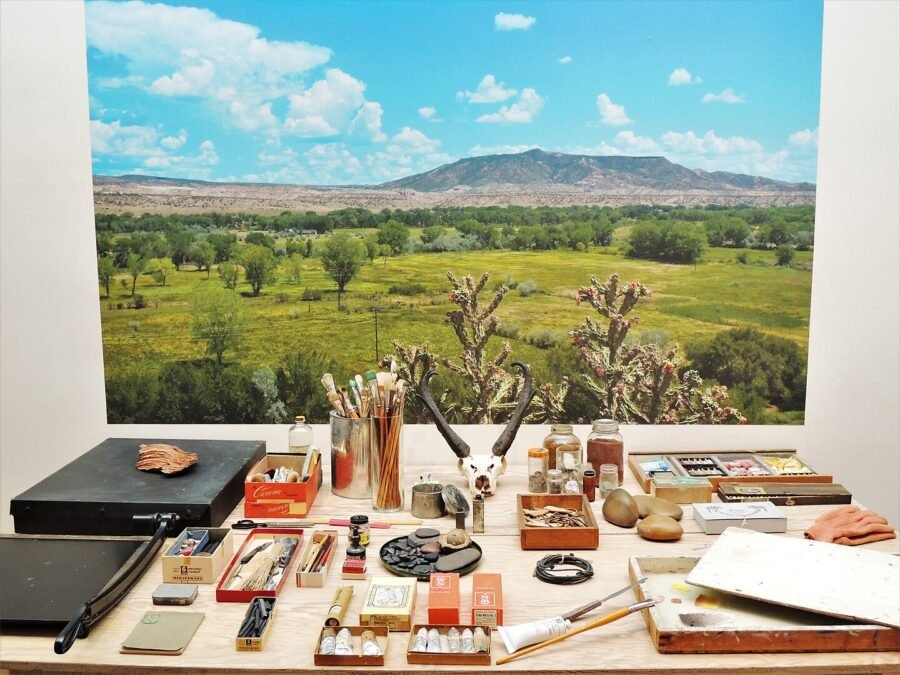

The museum’s collection includes nearly 150 paintings and hundreds of works on paper—ranging from pencil and charcoal drawings to pastels and watercolors. Visitors can also see personal items that shaped O’Keeffe’s daily life, from rocks and animal bones to dresses, paintbrushes, and a remarkable archive of documents and photographs that illuminate her world.

While the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum is the best place to connect her biography with her artistic practice, many of her most famous works are also housed in major institutions such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

This broad presence makes her art accessible to audiences nationwide, and I feel fortunate to have encountered her masterpieces in museums across the country.

Exciting News: The museum is planning an expansion, with a new building set to open in downtown Santa Fe in 2026. When completed, many major works currently on loan will return, offering an even richer experience for future visitors.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Learn more about the new museum project.

Painting materials as displayed at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico

The Abiquiú Home & Studio

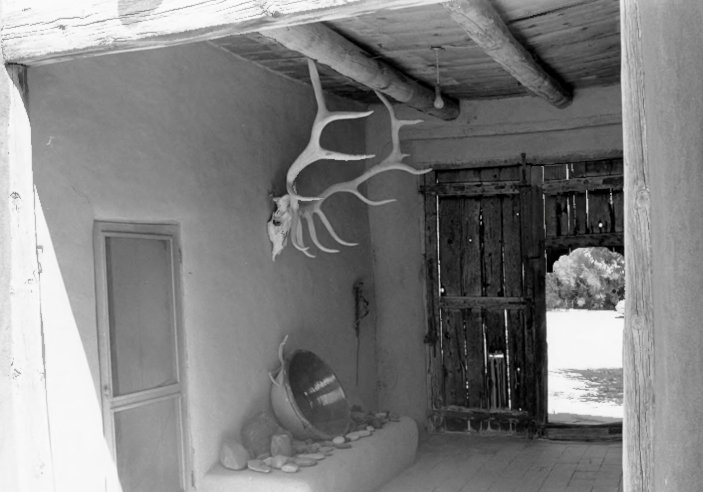

Georgia O’Keeffe Home, zaguan, side entrance/Zaguán von Georgia O’Keeffes Haus und Studio, Abiquiú, New Mexico

The highlight of my trip was visiting Georgia O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú Home & Studio, located about 50 miles northwest of Santa Fe. Tours begin at the welcome center, and I highly recommend joining one to gain a deeper understanding of her life, art, and the environment that shaped her work.

What about the Patio Door?

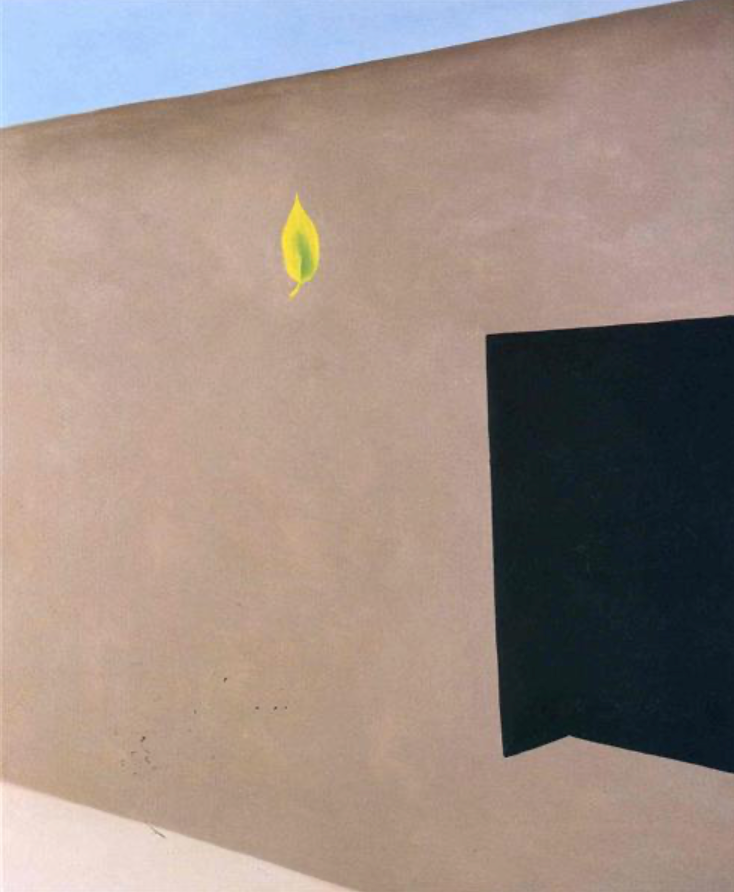

Georgia O’Keeffe, Patio Door with Green Leaf, 1956. Image courtesy of WikiArt

The guided tour was truly a revelation. As we walk through the interior courtyard, the guide pointed the recessed dark door into the adobe wall. (Unfortunately, I can’t share my personal photos due to photography restrictions.)

I learned that the patio door was the very reason for O’Keeffe to purchase this Abiquiú Home. She later confessed, “I bought the place because it had that door in the patio—the one I’ve painted so often. I had no peace until I bought the house.”

She painted it over and over – more than twenty times. Was it a canvas? Was it her imaginative black hole or space?

Perhaps the door was a metaphor for her inward gaze, a lens for a looking outward, and inward at the same time—something private, unknowable? She wrote, “…Making your unknown known is the important thing.” She emphasized the value of expressing what lies within, even if it is not fully understood.

It was a threshold between the world outside and her private sanctuary. It was a portal!

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú Home. Courtesy of National Park Service

Our knowledgeable guide shared intimate stories about O’Keeffe’s daily routines—her extensive collection of coffee-making gadgets (I’ve now decided not to feel guilty about my own!), her passion for making yogurt, her dedication to preserving vegetables from her garden for winter, and her love of music.

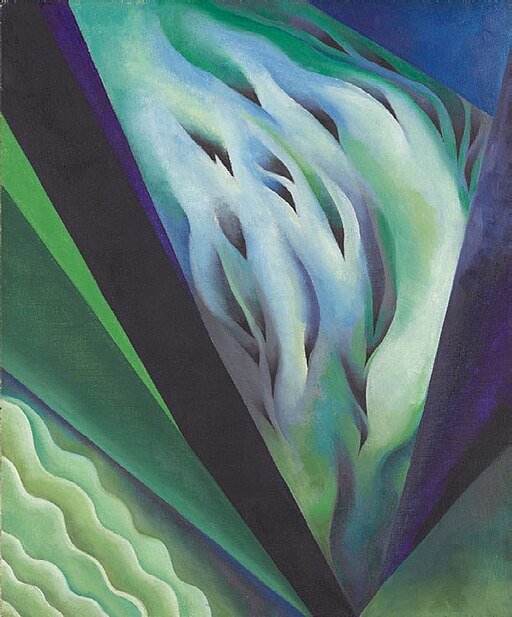

Fascinatingly, O’Keeffe was intrigued by the idea of translating music into visual art. This musical sensibility is evident in her paintings through rhythmic repetitions of lines, forms, and colors, creating a visual harmony akin to a musical composition (below).

Georgia O’Keeffe, Blue and Green Music, 1921. Courtesy of Art Institute of Chicago

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music Pink and Blue, 1918, Courtesy of WikiArt

I also learned about her passion for photography. O’Keeffe owned both Leica and Polaroid cameras, which she used as tools to sketch and study compositions. Viewing the world through a camera lens influenced her artistic vision—she saw bones, for example, as a kind of lens or viewfinder framing the sky and landscape.

The pinnacle of the tour was her studio, where panoramic mountain views flood through the windows. Being in this creative space gave me a profound appreciation for how her surroundings influenced her artistic process.

Note: Again, sadly due to copyright restrictions, I cannot share my own photos from inside the studio other than this. For official images and more information, please visit the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum website.

Ghost Ranch and the Land that Inspired Her

After Abiquiú, I made a quick journey to Ghost Ranch, where O’Keeffe owned a house and spent much of her time. Unlike the Abiquiú Home and Studio, Ghost Ranch is not open for public tours. Although I arrived too late to visit the museum, I was eager to experience the surrounding landscape firsthand.

The dramatic red rock formations and sweeping canyons were awe-inspiring. It’s easy to understand why O’Keeffe was so deeply drawn to this landscape—the colors, shapes, and vastness are unlike anywhere else.

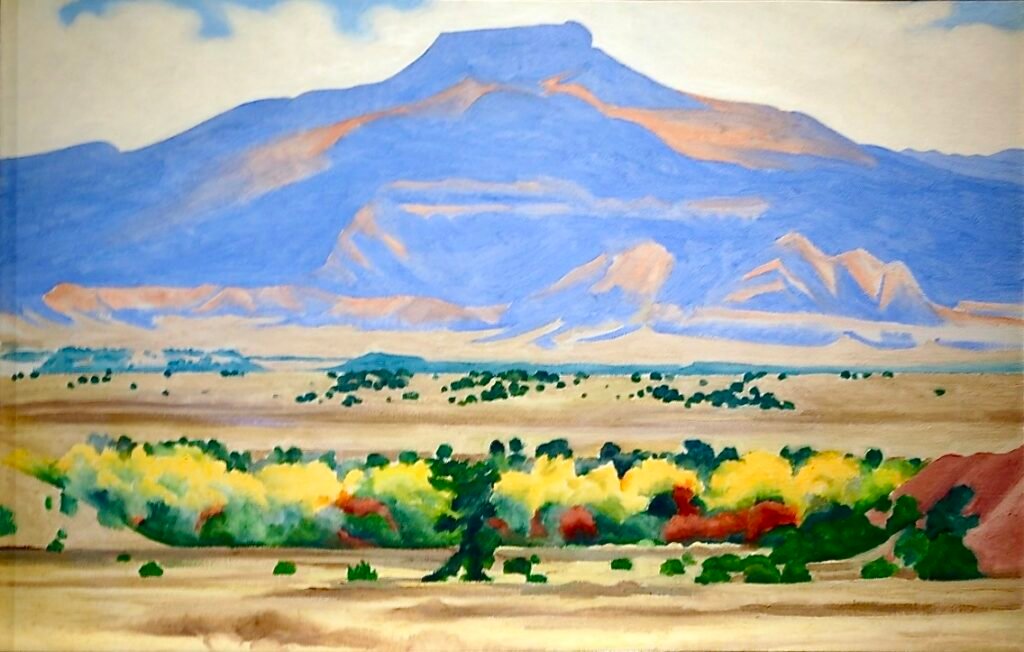

Cerro Pedernal, viewed from Ghost Ranch near Abiquiu, New Mexico | Artotem, Pedernal Mountain, NM, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0

Georgia O’Keeffe, Pedernal Mountain, Oil on canvas, 1941-1942, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum|Gift of The Burnett Foundation and The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation

One of the most iconic features of the area is the flat-topped mountain called the Pedernal, which O’Keeffe saw every day from her patio. She felt a spiritual connection to this distinctive landmark and painted it repeatedly. She famously joked, “It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.”

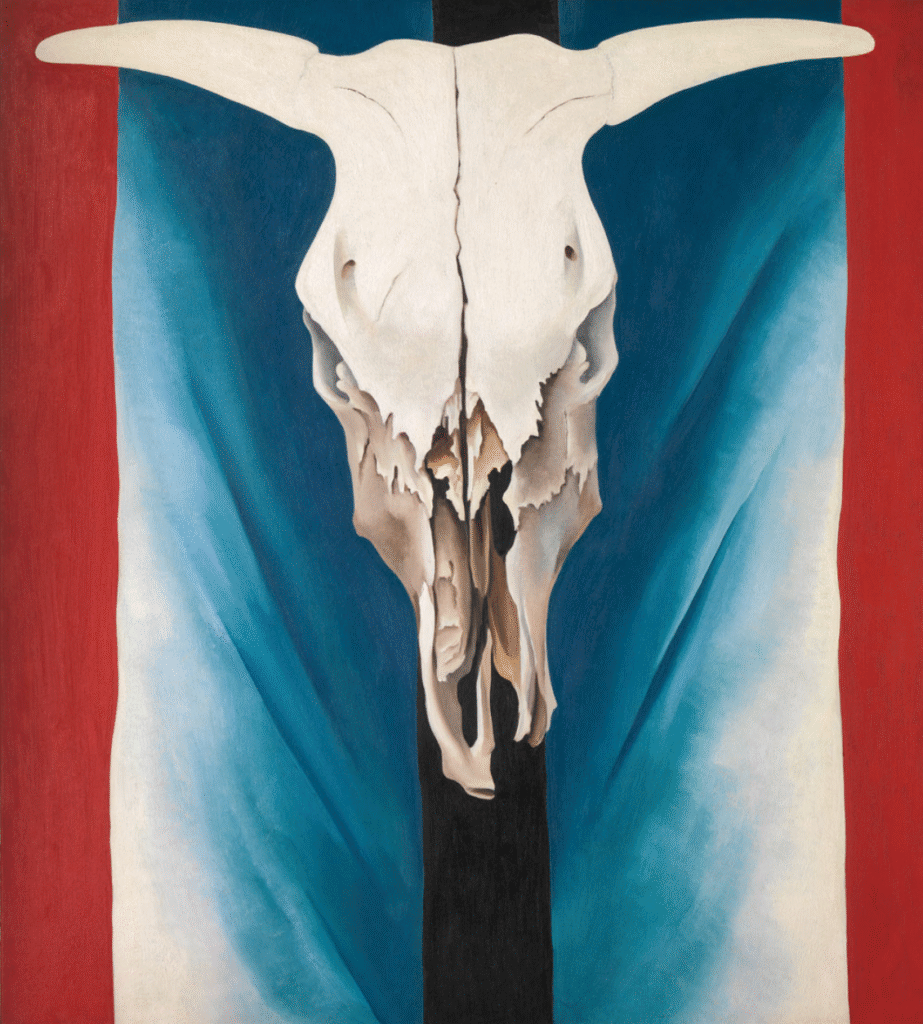

Ghost Ranch and the surrounding desert served as the backdrop for many of her iconic works featuring animal skulls and bones. Interestingly, some of these paintings were completed in New York (before she settled here) after she collected bones in New Mexico and brought them back to her studio in NY.

While exploring the park, I came across a small cottage marked “Georgia O’Keeffe’s Cottage.” Though I wasn’t sure of its exact use, it added a tangible connection to the artist’s presence in this rugged landscape.

Where Earth Meets Sky: O’Keeffe’s Paintings of Bones and Sky

Georgia O’Keeffe, Pelvis with the Distance, Oil on Canvas, 1943. Image courtesy of WikiArt

O’Keeffe’s fascination with animal bones began as a response to the stark beauty and symbolism she discovered in the desert. She described finding bones “clean and white, as if they belonged to the sky.” In her paintings, these bones often appear set against the brilliant blue of the New Mexico sky, creating a striking interplay between life, death, and the eternal.

Reflecting on her pelvis bone series, O’Keeffe explained:

“They were most wonderful against the Blue – that Blue that will always be there as it is now after all man’s destruction is finished.”

One of her most iconic works, “Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue” (1931)(Left), uses the skull as both a symbol of the American West and a testament to the endurance of life in harsh environments. O’Keeffe saw bones as “strangely more living than the animals walking around,” capturing the essence of the desert’s beauty and resilience.

Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue, Oil on Canvas, 1931, Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

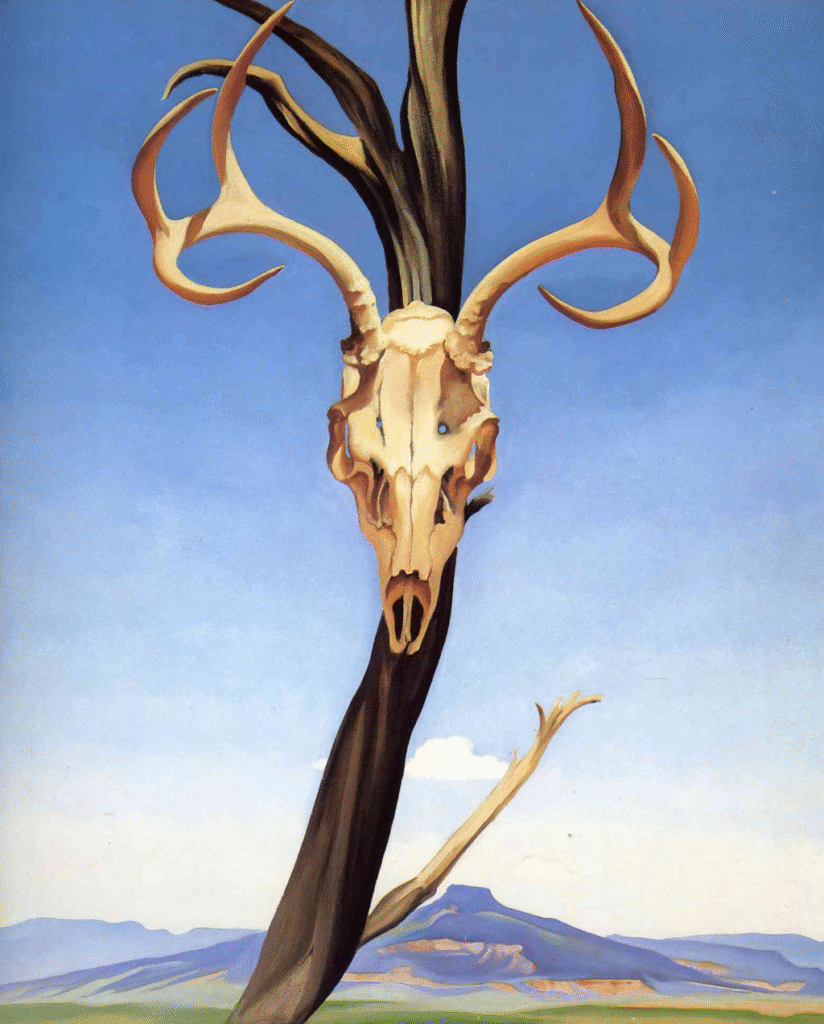

For me, her ability to combine seemingly unrelated elements—like in “Deer’s Skull with Pedernal”—is especially thought-provoking. The painting is representational, yet infused with a subtle surrealism. The ash-colored skull appears to float, suspended before a stark, skeletal tree and the brilliant blue sky.

Deer’s Skull with Pedernal, Oil on Canvas, 1936. Gift of the William H. Lane Foundation

This dark, skeletal trunk cuts across the vibrant blue sky, dividing the space with a bold curve. A small, broken offshoot mirrors the shape and hue of the antlers, creating a quiet visual echo that holds the composition in balance.

In the distance, the compressed, scaled-down Pedernal mountain intensifies the sense of spatial contrast, making the deer’s skull feel both monumental and vividly alive–—as if suspended in time, more alive in death than it once was in life. It’s a haunting yet harmonious fusion of landscape and symbol, presence and absence.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Goat’s Horn with Red, Pastel on paper laminated to cardboard, 1945. Courtesy of Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Through these works, O’Keeffe elevates bones and desert landscapes into enduring symbols. For her, bones and skulls were not mere remnants of the past, but portals—lenses through which earth meets sky, and the boundaries between mortality and the infinite. This vision continues to captivate and move viewers today.

Final Thoughts

Photograph of Georgia O’Keeffe, seen nestled on a cushion on the ground, with her sketchpad and watercolors by her side | Von Alfred Stieglitz – Phillips, Gemeinfrei, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31251732

Visiting O’Keeffe’s New Mexico was more than a journey through landscapes—it was a journey into the heart of her art. Standing where she stood, seeing what she saw, and learning about her daily life brought new depth to my appreciation of her work.

I hope this post inspires you to explore O’Keeffe’s art—whether in person, online, or through future posts in my “Follow Along” series on YouTube.

For more on Georgia O’Keeffe’s life and art, visit: