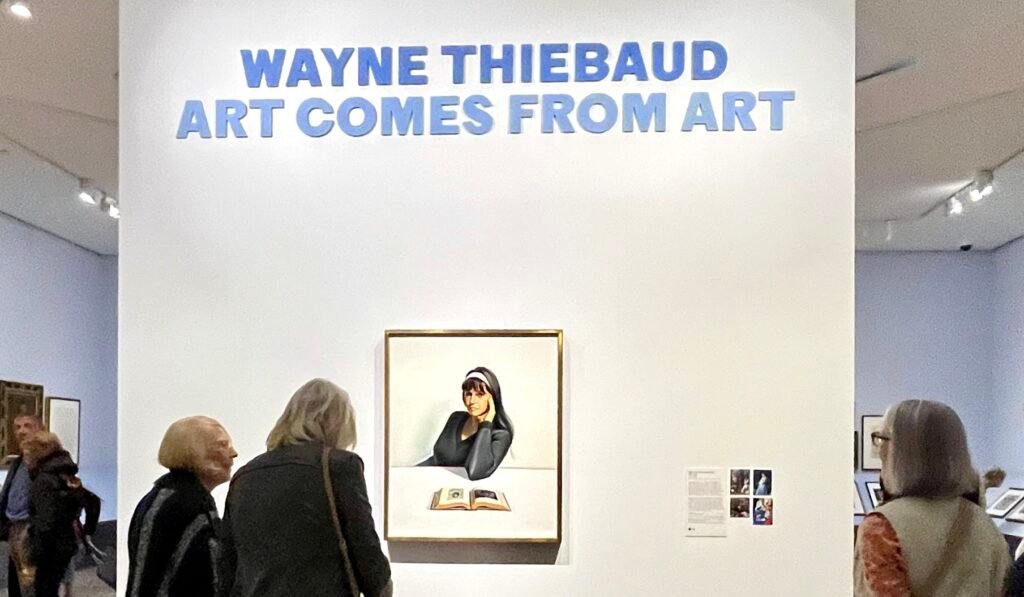

Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art

Serendipity at the Legion of Honor: My Personal Encounter

It was many years ago in San Francisco when I stumbled upon one of the most memorable mistakes of my life.

Scanning event listings in a local paper or magazine, I caught sight of a name that immediately pulled me in: Wayne Thiebaud at the Legion of Honor. Without reading another word, I dropped everything and made my way to the museum.

When I arrived, I was greeted by a pre-event reception featuring an unforgettable array of desserts — a scene that nearly echoed Thiebaud’s own iconic canvases. I then found a seat inside, only to notice a few of the organizers whispering and glancing in my direction.

One began to approach me before being stopped by the other. I signaled as if to say, “Is something wrong?” and was told, gently, that the event was intended for a senior group. Looking around, I realized with sudden embarrassment that I was the only young face in a room otherwise filled with elderly attendees.

To their credit, they kindly let me stay. And so, by happy accident, I had the extraordinary chance to hear Wayne Thiebaud speak. He was witty, quick, and endlessly charming — the audience erupted in laughter again and again.

The one remark that has stayed with me ever since was his insistence that he preferred to be called a painter rather than an artist, because, as he explained with a twinkle in his eye, “anyone can call themselves an artist.”

It remains one of the greatest opportunities I could have imagined — an unplanned detour that became a cherished memory.

Decades have passed since that unexpected afternoon. Recently, I found myself back at the Legion of Honor, this time under very different circumstances — after Wayne Thiebaud’s passing.

Walking through the galleries, I was overwhelmed by the joy of standing before so many of his masterpieces, and at the same time struck by the bittersweet reality that the witty, humble man I once saw in person was no longer with us.

It felt as if two moments in time overlapped: my younger self stumbling into his talk by accident, and my present self deliberately flying to San Francisco to honor the painter whose work had left such a lasting impression.

Focus of This Post: Thiebaud as an “Obsessive Thief”

Before diving into Thiebaud’s biography and stylistic analysis, let me clarify the purpose of this post: it is not simply to catalog Thiebaud’s signature subjects or techniques. Rather, I’m compelled by his philosophy of painting—his conviction that “art comes from art and nothing else.”

Thiebaud called himself an “obsessive thief,” meaning he saw artmaking as part of a rich, ongoing tradition of borrowing, reinterpreting, and transforming the achievements of others. He admitted, almost proudly, “it’s hard for me to think of artists who weren’t influential on me because I’m such an obsessive thief.”

Biography: From Cartoonist to Painter

“Wayne Thiebaud” by rocor is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Early Life and Foundations

Born in 1920 in Mesa, Arizona, Thiebaud was raised in Los Angeles. His early career as a commercial artist and cartoonist—including a brief stint at Disney Studios as an animator—shaped his visual instincts. That grounding in graphic clarity—bold outlines, stylized forms, and strong design—remained a hallmark of his painting style throughout his life.

A Life of Teaching

Thiebaud spent decades teaching—first at Sacramento City College and later at the University of California, Davis. Teaching wasn’t a side pursuit for him; it was central to his identity. For Thiebaud, teaching was also a way of learning. He was known to work alongside his students, often completing the very assignments he had given them.

In the classroom, as in the studio, he emphasized humility, discipline, and the craftsmanship of painting—values that left a lasting impact on generations of artists.

Late Bloom & Breakthrough

Thiebaud’s breakthrough didn’t come until his forties. In 1961, when he brought his now-iconic dessert paintings to New York, galleries initially rejected them.

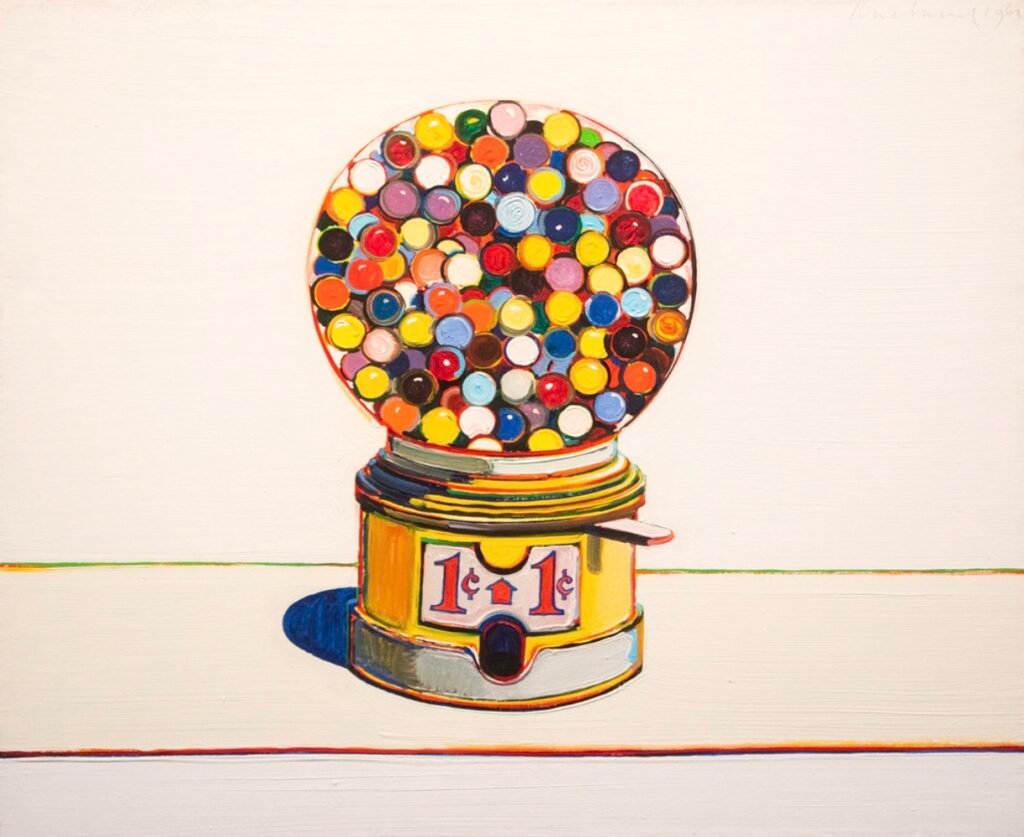

Dealers dismissed his subject matter—cakes, pies, lipsticks, gumball machines—as unserious. One called him “nuts.” But when Allan Stone Gallery took a chance on him in 1962, every work in his first solo show sold. From that point, his reputation soared.

Developing a Signature Style and Subject

Visual Language

Wayne Thiebaud, Display Cakes, 1963 (detail showing texture). Oil on canvas. Photo by Rocor via Flickr, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Wayne Thiebaud, Cakes and Pies, 1994–95 (detail showing shadows). Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of WikiArt (for educational use)

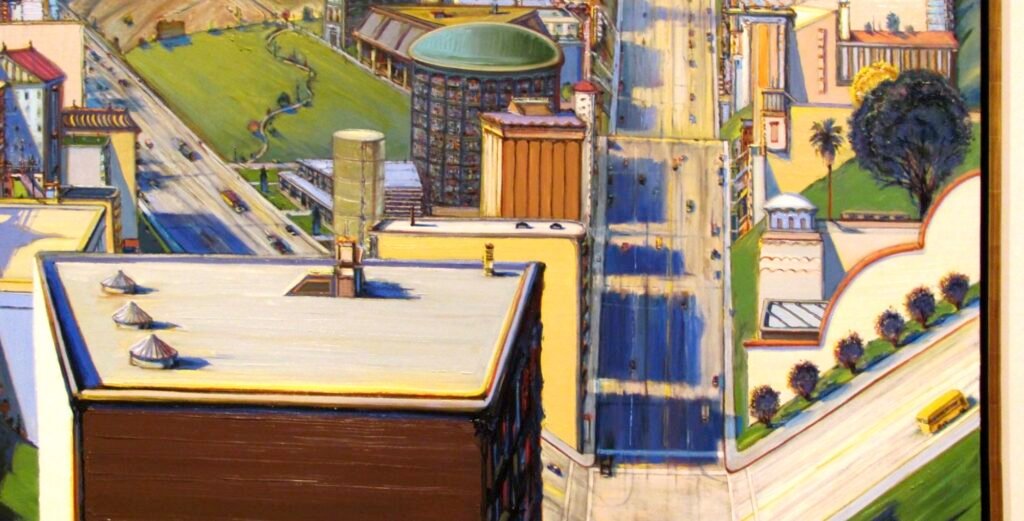

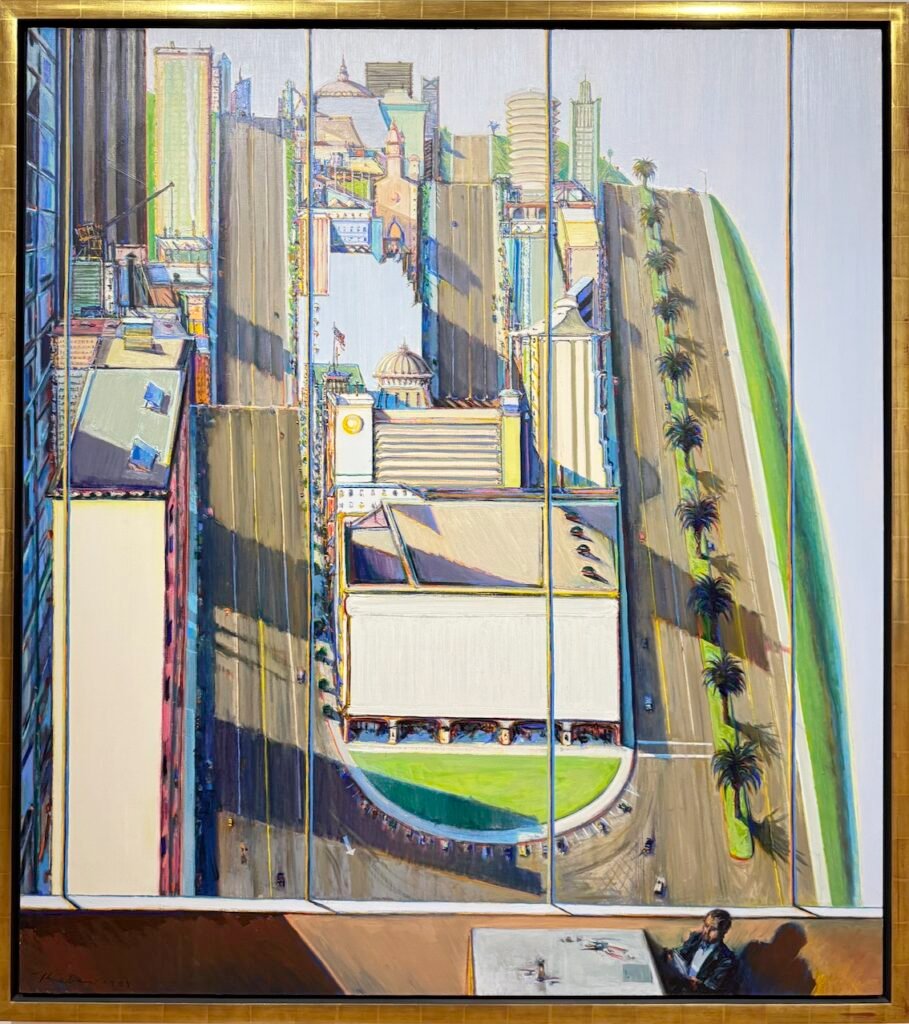

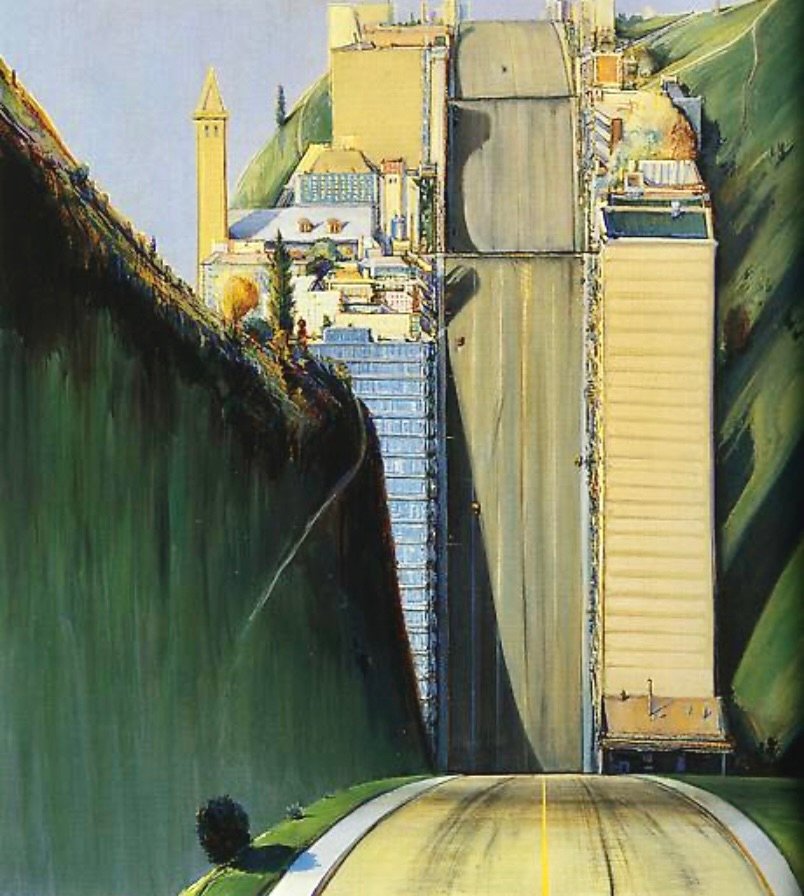

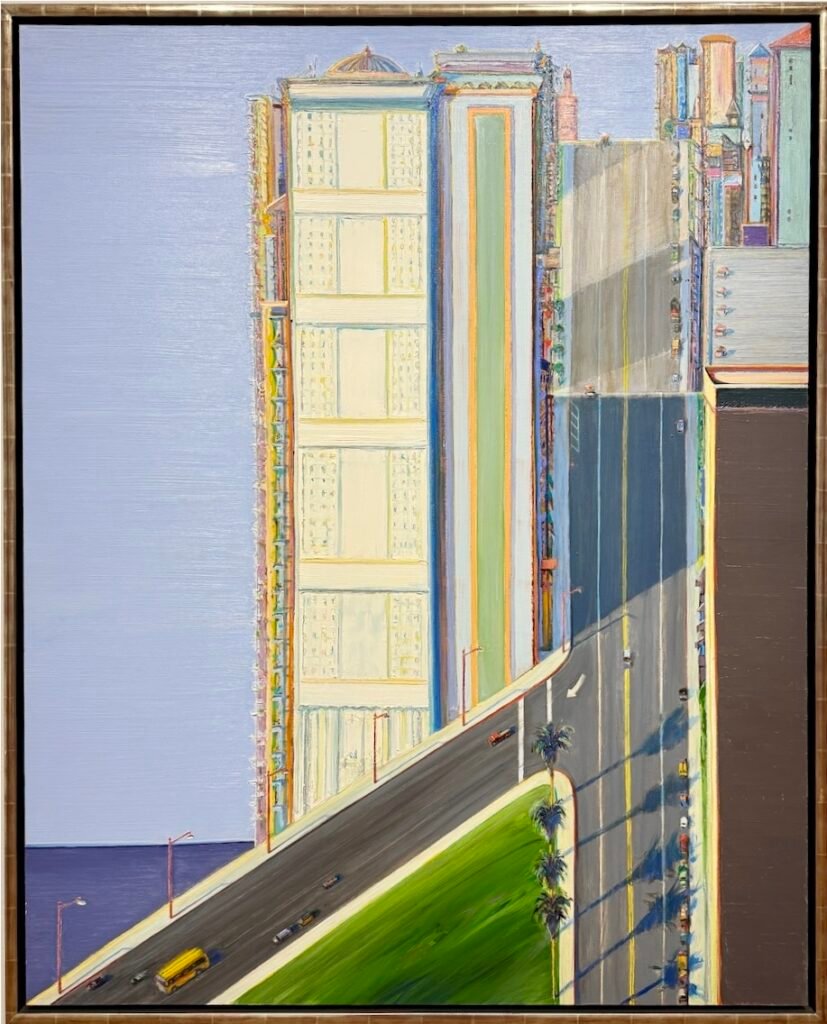

Although Thiebaud constantly sketched, he didn’t paint directly from observation. His cityscapes, in particular, are exaggerated, imaginative interpretations—often drawn from memory. Viewers have frequently tried to identify exact locations in his paintings, but such efforts are usually in vain.

Wayne Thiebaud, Park Place, 1993. Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of WikiArt (for educational use)

- Thick, textured paint – often compared to frosting, applied in rich impasto.

- Non-naturalistic shadows – pinks, purples, blues that heighten visual interest.

- Repetition with variation – especially in rows of desserts, each slightly different.

- Invented cityscapes and landscapes – inspired by memory and imagination, not direct observation.

- Geometric abstraction – compositions often bordered on the abstract, though always grounded in the familiar.

Pop Art and Beyond

Because of his choice of subject matter, Thiebaud was often grouped with Pop Art and exhibited alongside figures like Warhol and Lichtenstein, whose works critiqued consumerism. Yet Thiebaud resisted the label, objecting to what he called the “mechanical” quality of much Pop painting.

Interestingly, his dessert paintings slightly predated the canonical works of Pop Art, raising the possibility that Thiebaud’s approach may even have influenced the movement.

Unlike his Pop contemporaries, Thiebaud celebrated the ordinary with affection rather than irony. He preferred to describe himself as “just an old-fashioned painter,” one more concerned with form, color, and the American still-life tradition than with commentary on consumer culture.

Art Comes from Art: Creative “Theft” and Legacy

Sources of Influence & Exchange

Thiebaud’s influences were vast:

- Lessons from commercial design

- Profound inspiration from European modernists and American scene painters (Cézanne, Morandi, Bonnard, Hopper)

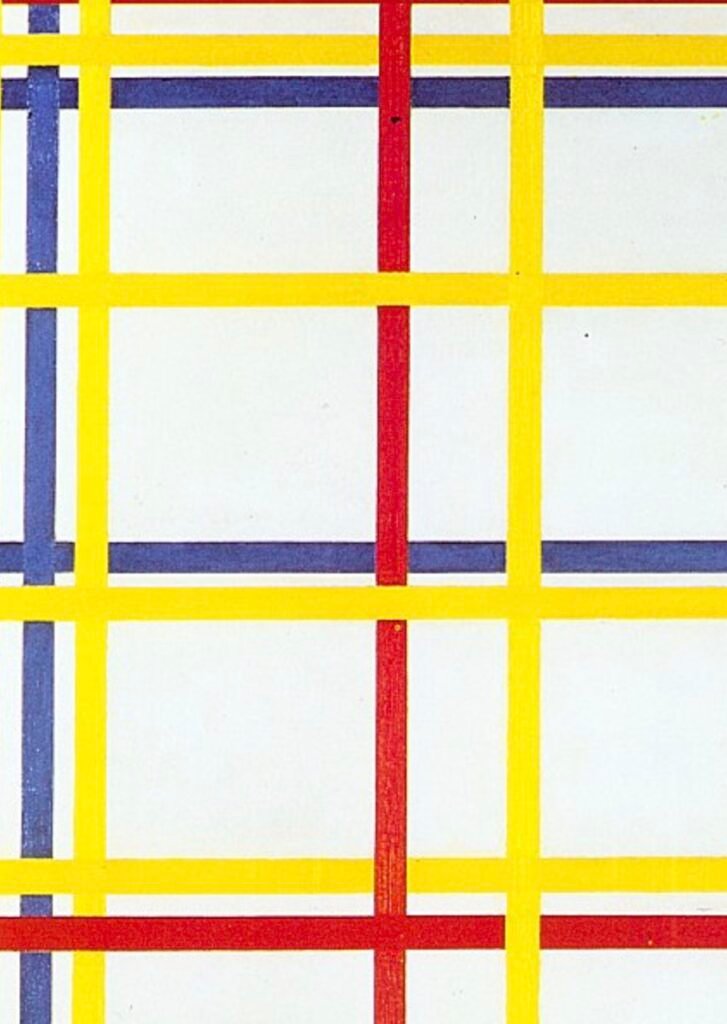

- Compositional insights absorbed from Mondrian, Degas, Matisse

- Collaborative exchange with California artists like Richard Diebenkorn and Robert Arneson

Yet, despite these influences, Thiebaud’s style remained singular: playful, refined, deeply personal. He avoided alignment with any single movement, forging his own path.

Reflections on the Exhibition

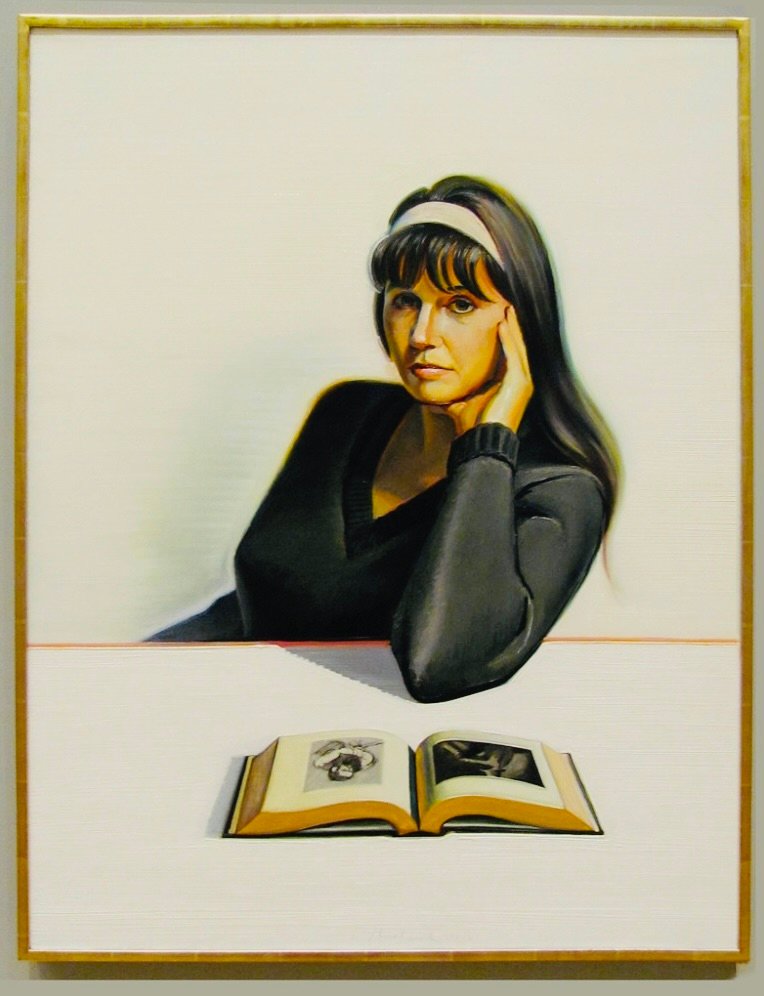

At the entrance of the exhibition, my eyes were immediately drawn to the striking painting Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book, which depicts Thiebaud’s wife seated with an open volume, one page showing drawings by Edgar Degas and the other by Georges Seurat, suggesting that its very composition may have been inspired by the work of past masters.

Thoughtfully placed by Timothy Anglin Burgard, Curator in Charge of American Art, this work seemed to distill the essence of the exhibition: a visual and symbolic reflection of Thiebaud’s deep engagement with art history and the central theme of his self-described role as an “art thief.”

The exhibition also included select works from Thiebaud’s personal art collection. Throughout his life, Thiebaud actively acquired and traded for pieces by artists he admired—both historical and contemporary. Surrounded by originals from Rembrandt, Ingres, Matisse, Joan Mitchell, and others, he engaged in a direct dialogue with their work. His collection wasn’t just for admiration; it became a source of study and a catalyst for his own creative exploration.

Featuring over 100 works—spanning still lifes, figures & portraits, cityscapes, and landscapes—the exhibition overwhelmed me with its breadth and depth. What fascinated me most were Thiebaud’s reinterpretations, presented alongside reproductions of the masterpieces that had inspired them.

Discovering that so many of Thiebaud’s seemingly familiar images were rooted in historical references was both powerful and humbling. It offered not only a fresh way of seeing Thiebaud’s work but also a profound reminder: drawing from the past can be a rich source of inspiration for any artist.

As the exhibition title Art Comes from Art suggests, Thiebaud believed that “art comes from art and nothing else.” To him, the history of art becomes a timeless conversation, where works from every era speak across centuries, offering endless echoes of inspiration.

Thiebaud’s Philosophy of Appropriation

What made Wayne Thiebaud unique wasn’t just his subject matter—pies, cakes, gumball machines, San Francisco streets—but his openness about artistic influence. He believed that appropriation was not only acceptable, but inevitable.

“The more I got interested in layout and design, the more I was led to those examples in fine art from which they were derived. The most interesting designs were influenced by Mondrian or Degas or Matisse. That revelation really transfixed me.”

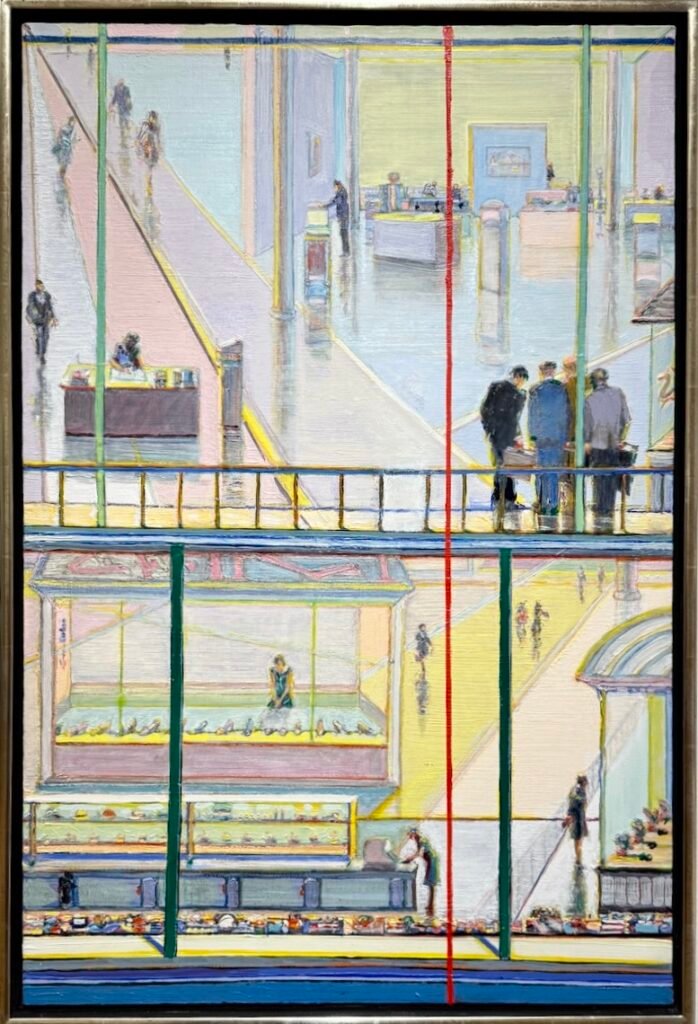

Thiebaud’s structural grids and candy-colored planes recall Mondrian’s geometric abstractions, yet he reimagined them within the bustling interiors of modern life.

Thiebaud didn’t hide his influences; he studied and reinterpreted them. In Office and Shopping Mall (2005/2021), for example, the crisp grids and intersecting planes recall Mondrian’s compositions—but with Thiebaud’s signature distortions of perspective and candy-colored palette.

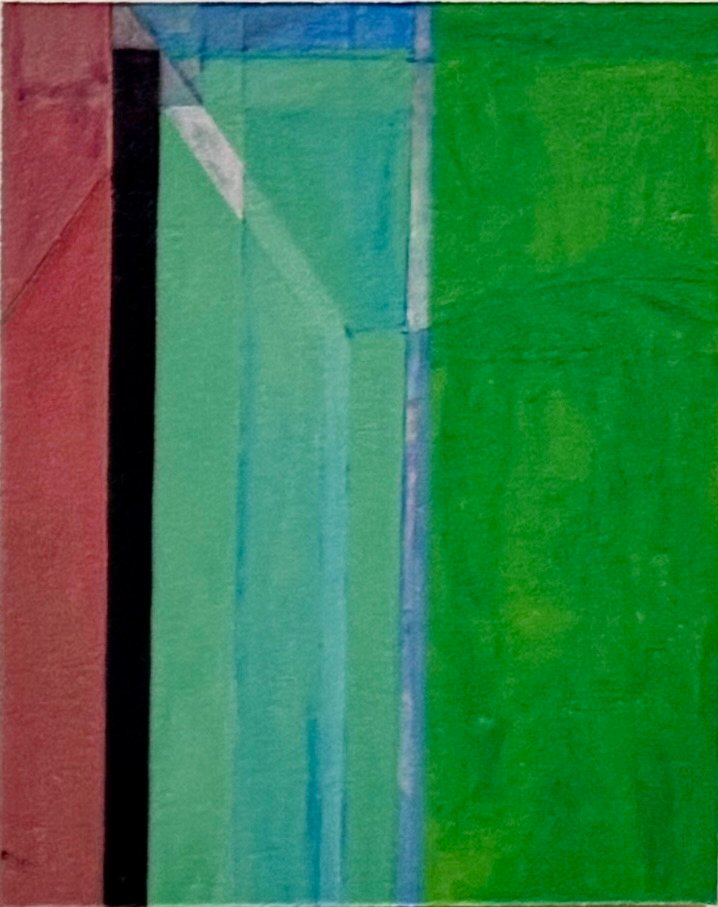

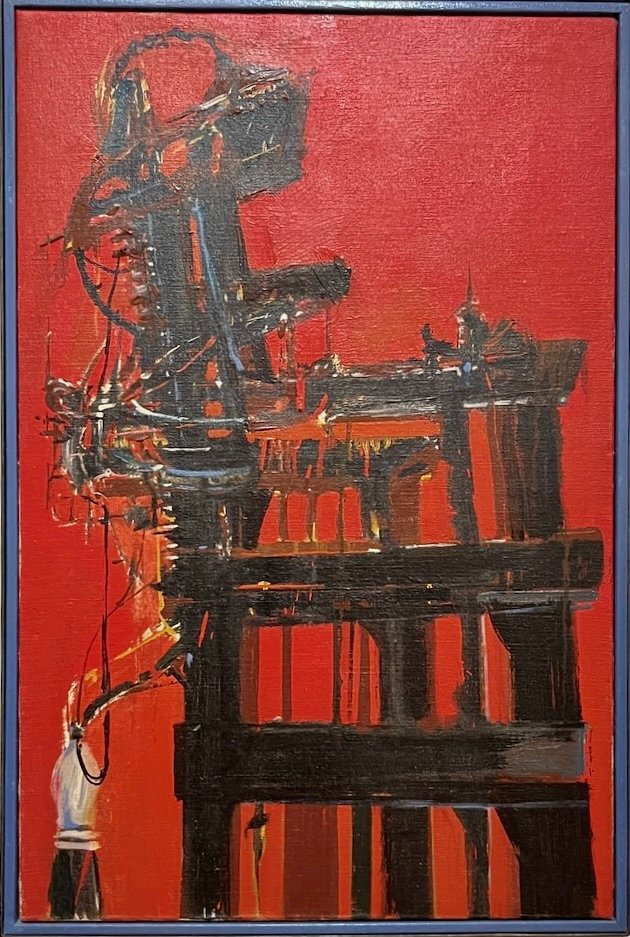

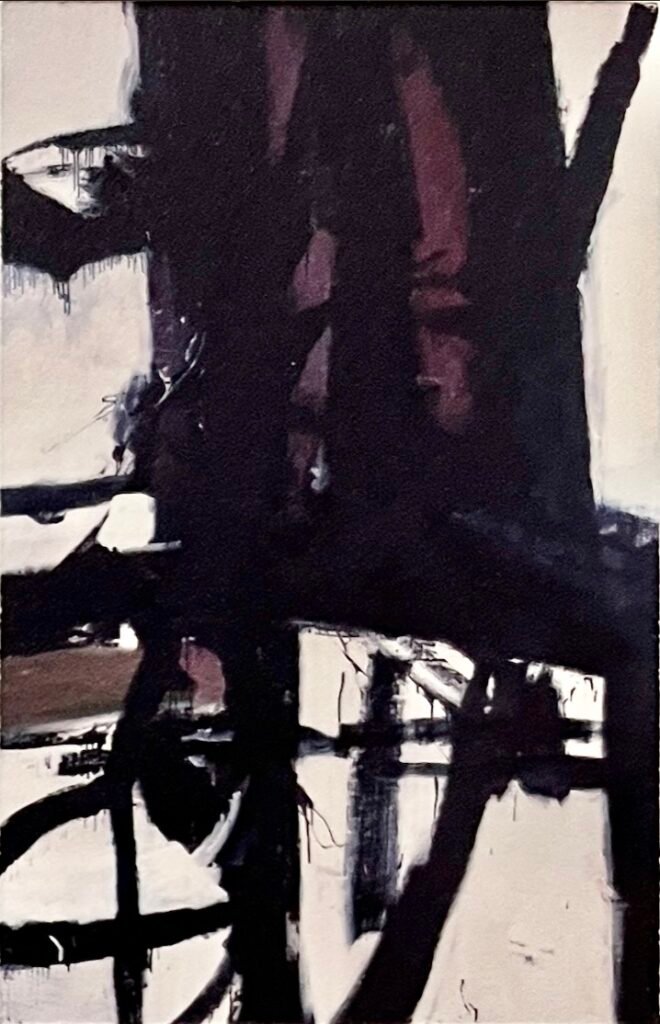

Another artist Thiebaud deeply admired was Richard Diebenkorn, particularly for his ability to blend abstraction with representation. In Thiebaud’s cityscapes and landscapes, the influence is unmistakable in their spatial structure.

Thiebaud not only admired Diebenkorn’s compositions but also his palette. He especially appreciated how Diebenkorn captured the unique luminosity of California light, a quality that resonated deeply in Thiebaud’s own use of color.

Giorgio Morandi was another artist Thiebaud deeply respected. From Morandi, he learned how ordinary still-life objects could be transformed into something quietly dramatic through a masterful command of light, composition, and pictorial tension. Morandi’s ability to charge simple forms with emotion left a lasting impression on Thiebaud.

Building on that foundation, Thiebaud elevated his own everyday subjects—gumball machines, cakes, pies, and lipsticks—taking the idea of the commonplace to a new level and developing a visual language entirely his own.

One detail that particularly stood out to me was in Confections (1962). The creamy swirl on top of the sundae—almost as if a finger had just pressed into it—made me want to reach out and sneak a taste, then lick my finger. That small, playful gesture brought a smile to my face and immediately reminded me of Thiebaud’s wit during the talk I attended years ago.

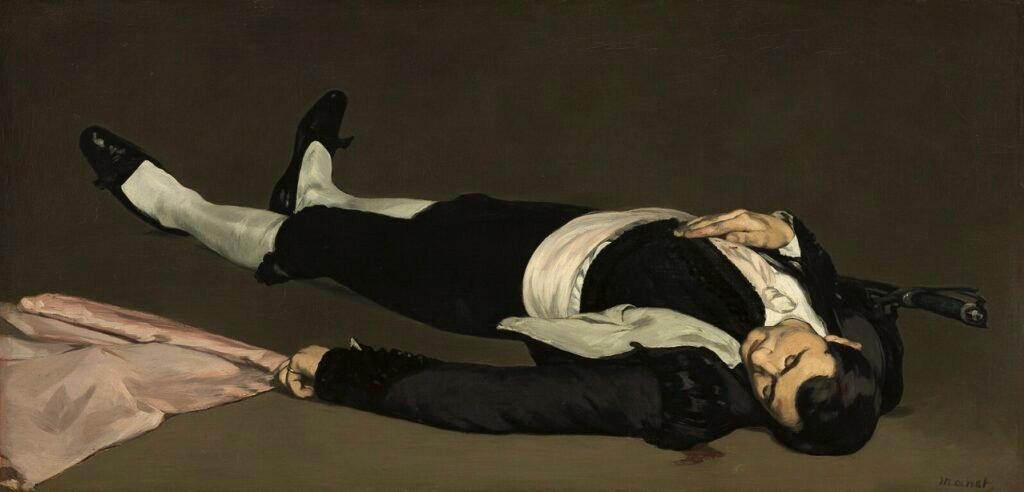

Edouard Manet, The Dead Toreador, 1864-1865, Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of National Gallery of Art

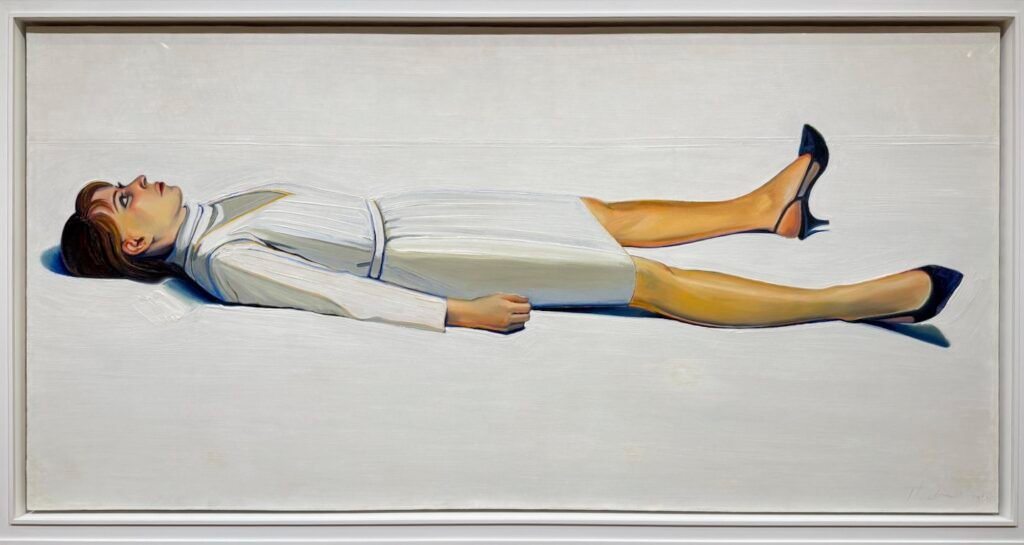

Wayne Thiebaud’s Supine Woman (1963), an oil on canvas depicting his daughter Twinka, reveals both his debt to art history and his willingness to push beyond tradition as Manet also did.

While the painting acknowledges the influence of Manet’s Dead Toreador, Thiebaud transforms the subject into something wholly his own. Instead of a fallen bullfighter, we see a young woman, starkly foreshortened, isolated against a flat white ground.

I learned that Twinka originally posed in a black dress, but Thiebaud chose to render her in white on white, heightening the work’s formal severity. Her wide, unblinking eyes and the deliberate absence of narrative detail create a chilling ambiguity — somewhere between a portrait, a still life, and an experiment in modernist form. The result is both unsettling and radical, a bold departure that demonstrates Thiebaud’s lifelong pursuit of new ways to reimagine the figure.

Crucially, his goal was never mimicry. He believed influence could generate originality, creating what he called a “different visual species” of art.

He believed progress in art is “variation, yes, and extension… but progress? I don’t know how you’d beat any of that stuff, even from the cave period.”

His 2025 exhibition, Art Comes from Art at the Legion of Honor, embodied this philosophy. It showcased reinterpretations, direct copies, and thoughtful variations—often displayed alongside the historical works that inspired them—making the lineage of influence visible, and vital.

Thiebaud‘s Vision: A Legacy That Still Resonate

Thiebaud’s methods, mischief, and humility offer not only inspiration but also a reminder: greatness often begins with appreciation—and leads to transformation—of the world and the art around us.

His legacy stands on three enduring pillars:

- As a painter who transformed humble subjects into luminous icons.

- As a teacher who shaped and inspired generations.

- As a thinker who showed that originality grows from honest influence.

He received the National Medal of Arts, major retrospectives at the Whitney and SFMOMA, and painted almost until his passing at 101. Yet he remained humble, always calling himself a “painter” rather than an “artist.”

Lasting Lessons for Artists and Viewers

As creators, we are constantly searching for new ideas. Thiebaud’s example reminds us that inspiration rarely arrives out of thin air—it comes from looking closely: at art, at life, and at the work of those who came before.

This Thiebaud’s approach—engaging directly with historical works—can serve as both a model for education and a method for artistic practice. For artists and students alike, it shows how influence, when approached with intention and respect, can fuel originality rather than diminish it.

He redefined “stealing” not as theft, but as tribute—a way of keeping painting alive through dialogue and reinterpretation.

For me, the memory of that afternoon at the Legion of Honor—stumbling into his talk, laughing at his wit, hearing him claim the word painter with pride—has become inseparable from my journey to revisit his work after his passing.

Thiebaud continues to teach me that joy, reverence, and even a little “thievery” can be the most honest ways to keep creating.

*Curious to learn more about my visit to the Legion of Honor and de Young Museum? Click to read my full reflection and see the highlights.

Upcoming Exhibition in the UK

If you missed the show here, there’s fantastic news: The Courtauld Gallery in London will host The Griffin Catalyst Exhibition: Wayne Thiebaud. American Still Life—the first-ever museum exhibition of Thiebaud’s work in the UK—from 10 October 2025 to 18 January 2026.